You may have noticed that a lot of new audio coming from record companies and music services sounds heavily compressed, distorted or clipped. When you look at these audio files as a waveform, you can see the clipping, especially when comparing it to music from just 10 years ago, whether from the record company or a service like TM Century.

This article is about the quality of audio radio stations are receiving from music providers today.

To put this together, I spoke with numerous people in our industry, including three experts at well-known audio processing companies mentioned below, to get their take on what’s happening and how we can provide great audio to listeners.

What I found is that there is no single answer. But these experts agreed that it’s a problem and that quality is an issue.

Everyone has their own take on how to process audio that is (to put it plainly) either recorded too hot and clipped or processed out the wazoo to begin with.

Part of the problem with dealing with audio is not simply the fact that it’s frequently hot and clipped, but we are intermixing great audio with full dynamics (from older content) to our own studio material along with newer, highly processed content.

Where do you start and how do you set your processing when your source material is so inconsistent? If you process for new content, your old stuff could sound lifeless. If you process for old content, your new material may have no dynamic range (or feel processed out that wazoo).

Challenges

If we start at the beginning, we know that getting music for radio stations can be a challenge, unless you’re a major-market station with record companies still interested in getting that airplay.

Smaller stations may have to be creative in finding music including subscription services. This isn’t to say that music isn’t available all over the web, and there are some “non-paying” ways to acquire music (not recommended) from posted videos and download sites.

These are not necessarily legal ways to find music; they also may be compressed or have had multiple types of compression reducing the quality to that of a “personal MP3 player” … or even worse.

In the past, there were some great music providers that are no longer in the game (like the old TM Century), and record companies provided music with great dynamics and counted on the radio station to really do their processing on the playback end. Today, there are DJ music service and paid content download sites, but I believe most of us find these files highly processed or even clipped (see examples).

As a bit of an audiophile, I pay attention to quality. I truly want to see dynamic range and peaks that more resemble analog audio than a file with a minimal amount of dynamics and an apparent “flat lining” or clipping of the peaks.

For one thing, I always recommend staying true to “CD quality” with WAV-only files that come from CDs or uncompressed as original WAVs and never converting an MP3 to a WAV. As in life, you will not get something for nothing by turning an MP3 into a WAV. It’s still MP3-quality with just a different suffix to it.

In radio, we process (some more than others) for a multitude of reasons. First, since radio is often listened to while driving we want to overcome the background sounds or “road noise” by bringing up quiet passages without completely destroying the song’s dynamics. We also want our music to have “more punch” than other stations or other sources available to the listener.

Basically, many of us want bigger, brighter, louder and more punch. Considering FM’s own high-frequency limitation of 15 kHz, we have a slight disadvantage to the quality of a stream, but the advantage of something a little more “pure” or “real” in the fact that it’s not being “squashed” for streaming (plus the lesser chance of any “digital weirdness”).

We really could go back and forth on advantages (radio goes anywhere) and disadvantages (e.g., multipath) of radio, but paying attention to the quality of our files is a great starting point. It’s simply because we can never get any better than the quality of the original file.

Comparisons

Recently I’ve begun comparing audio files from TM Century’s old Gold Disc files versus a current music service. I’m shocked at what I found.

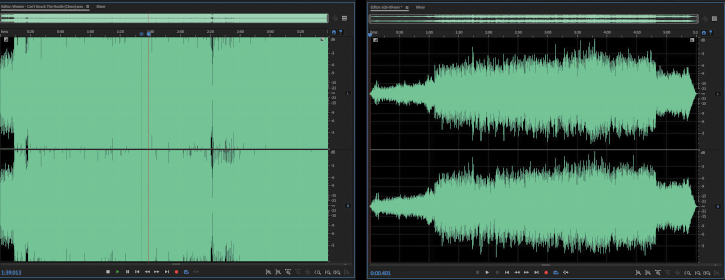

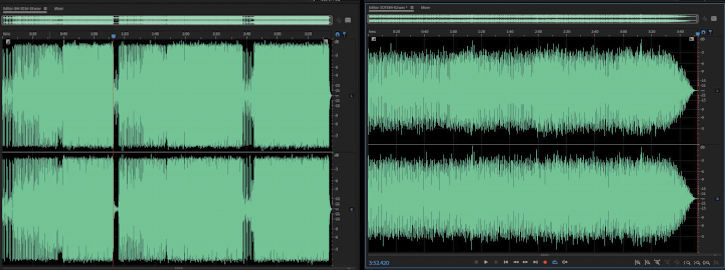

Let’s compare a few WAVs to show what I’m talking about. To do this, I’ve used Adobe’s Audition to open both files. No changes were made to any setting, and the screenshot is taken from unaltered editing images. All of these files are native WAV files, no conversion, no normalizing, nothing changed for what you’ll see.

First, a new song by Weezer called “Can’t Knock the Hustle,” followed by U2 and “Where the Streets Have No Name.” See Fig. 1.

You can see the difference, but what are we seeing? There appears to be so much processing on Weezer that there is very little left of the dynamics of the music. In other words, everything is loud! And what happens when we process it? The smallest amount of dynamics that were left are completely eliminated.

What does this translate to? Most program directors and consultants would likely say it will be loud on the radio but it will possibly be distorted or clipped, and that feeding this to a listener will likely result in “listener fatigue.” Simply put, our ears need those dynamics because they aid in providing an ear break.

More Songs

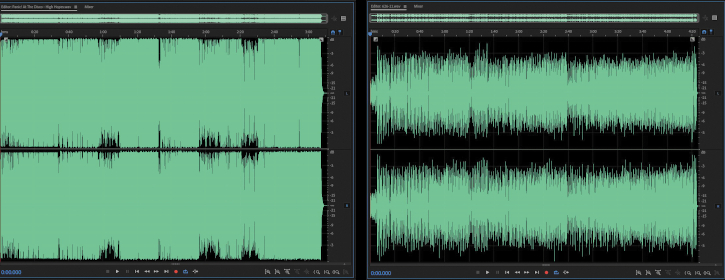

This is Panic at the Disco and Def Leppard (a generally “loud” group). Again, a very noticeable difference in processing and dynamics. See Fig. 2.

Switching gears, another newer song (from 2016) was DNCE’s “Cake By the Ocean” and The Romantics’ “Talking in Your Sleep.” Again, heavily processed but with a little more dynamics versus what appears to me a more heavily processed older song. See Fig. 3.

What is our takeaway from all this? Though this is just three examples, I’m finding new music generally follows these two examples. What I’m seeing is very little in terms of dynamics, some aggressive processing (which includes clipping) and a much different sound.

I spoke with a producer at the company that distributed the first two newer examples and specifically asked if they are doing processing; his response was that they are doing nothing to the audio files and these are coming from the music companies this way.

This leaves us in a bit of a quandary. For a new music-based station (playing lots of current pieces but with older material as well), we might find that to “keep the playing field level,” we may need to preprocess the old song files prior to air (something I generally never do other than trim the front and back when needed), increase our mic processing and reduce our own overall main processing.

This also should make us aware of the potential impact on our listeners and their own “ear fatigue” with the content we air. If we are seeing shorter listening time and playing newer music, we might ask if the younger audience has a shorter attention span, or if we’re simply killing their ears with overprocessed material.

I spoke with three well-known radio audio processing gurus — Bob Orban of Orban Audio, Frank Foti of Omnia/Telos and Jeff Keith at Wheatstone. I heard a consistent theme: Audio is coming in much louder than it ever did. Ironically, this negatively affects the louder portions of the audio. The dynamic range is eliminated.

An additional lesson is that it’s a good idea to bring the overall audio levels of the new content down (the amount varies according to who you ask).

That is something we all know they would do, and that we can appreciate. I’d certainly like to tell you which one is right and which solution is best, but that would be like me telling you which color is best. A lot of this is subjective, and much of it can also be proven by test gear. But the results of the test gear also can be open to interpretation. So when it comes to the available products by our audio processing companies (any of them), a lot will be left up to the individual and also how that processor sounds in their own air chain.

Exploring

Consider exploring your audio files and weighing your processing vs. the content and the variation between the audio files. Be sure that all audio files you air are consistent in level. This, at least, is an excellent starting point. Depending on whom you ask, –2 dB down or even more may be the point where you want all your audio files to reside. Ultimately, the determination of whether you preprocess audio files prior to your on-air (or streaming) audio processor is a call you will need to make.

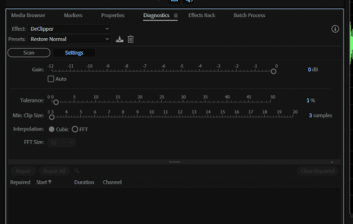

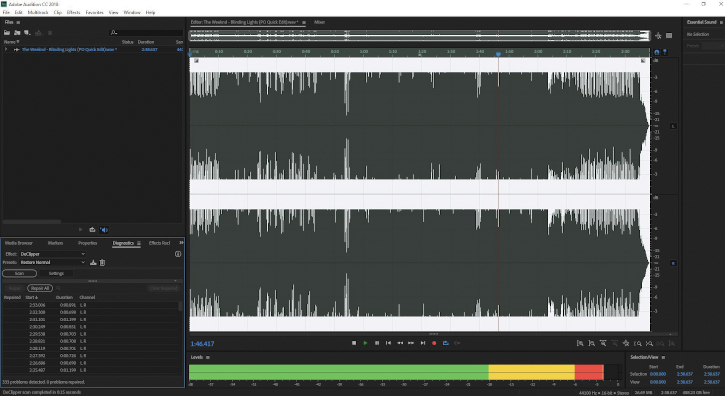

By using audio editing software, it’s possible to dig into the waves to really see what’s happening. Using Adobe Audition, I first look at the properties of the file and scan it under “Diagnostics.” There are presets under “DeClipper,” but I found one that allows for some peak restoration. I start with reducing the file by –2 dB prior to running the Diagnostic DeClipper. After it indicates errors (newer audio files can have hundreds, while material like that from the old TMC Gold Discs usually have none), I run Repair.

At that point, I go with a percentage and “normalize” the audio to –1 dB down. This reduces everything equally so only the peaks hit –1 dB. By doing this, I know my processor (both on-air and streaming) will be seeing consistent levels. See Fig. 4.

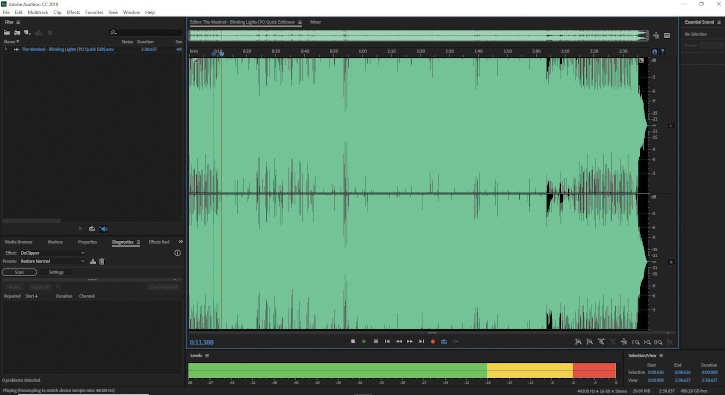

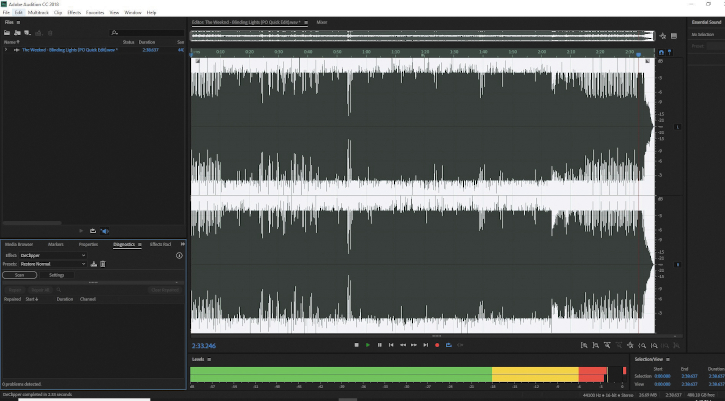

A file may start out looking like this example. The following is a song “as delivered” by the music provider. You can see how extreme the level is. The song is “Blinding Lights” by The Weeknd. See Fig. 5.

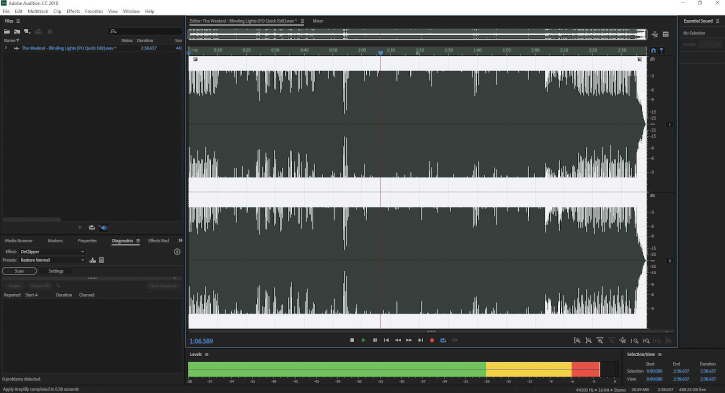

The same song reduced by –2 dB (Fig. 6).

Then the song is analyzed to find what Audition recognizes as clipped areas. Audition noted 333 errors (Fig. 7).

And finally, a –1 dB reduction overall and “the fix” is applied. This is how the resulting file looks (Fig. 8).

It’s better than what it was, and audibly has a cleaner, “less crunched” feel to it.

Unfortunately, these highly processed audio files (intended for broadcast) seem to be the norm. This forces us to really consider all of our audio content and how to process it. It also requires us to think about our own recordings including commercial and PSA production audio files.

How does recently produced material stack up compared to old music audio files? What about in comparison to currently produced music? How we preprocess the audio we pass off to our audio processors needs to have consistency.

The manufacturers of our processing gear recognize what we are dealing with and they’re using their own magic to help us maintain great audio for our listeners as well. Just keep in mind that they all have slightly to greatly different ways of doing this, so your ears (and those of possibly the music director, program director, operations manager, general manager, et al) may want to weigh in on this.

And don’t forget that webstream audio will very likely differ from the air audio, so be aware that all your audio should be considered when it comes to processing and preprocessing.

Dan Slentz has been chief engineer at radio stations from Athens to Zanesville (Ohio), and Dallas to Denver. He is also an Air Force vet who worked with Armed Forces Radio & TV from 1986–90 in Spain.