Chicago is very much a competitive PPM market. While it is hard to be perfect, seconds of off-air time are costly, and minutes of off-air time are just not acceptable. If you’re not on the air with PPM encoded audio, you are losing ratings.

Handling emergency audio situations has evolved considerably since I first came to manage the engineering department here at Crawford Broadcasting’s Chicago operation six years ago. I remember early on that there seemed to be no plan. When something out of the ordinary occurred, like the automation system stopped playout, the operators seemed to have no plan what to do.

When this type emergency occurred, if it was a time when engineers were on duty, they would leave the room to try to find an engineer without putting anything on the air first.

Many times, when I walked into a control room, the staff would be throwing their hands in the air, saying something like, “I didn’t do anything!” to which my reply would be, “You’re right, you didn’t do anything!” In other words, why were you not getting any audio on the air before seeking or calling an engineer?

To me the priorities of every operator should be, Number One, making sure no objectionable material gets on the air — we don’t want a $325,000 fine — but Number Two, keeping the meters moving! It’s a competitive PPM market, and the minutes waiting to find an engineer to fix the issue are just not acceptable. The duty of every operator is to make sure we have audio on the air, then call engineering to get things fixed and back to normal audio.

About the only plan that seemed to exist among the operators was perhaps to find a CD to put on the air. Often, they didn’t know where the emergency CD was located, or they didn’t even know such a thing even existed.

Basically, there was no plan, and very little training for such events. The plan seemed to be call engineering and throw up your hands to make sure everyone knows it wasn’t your fault.

A few years back, we purchased USB thumb drive players to place at the transmitter sites for emergency audio. Using silence detection and macro programming in the Burk ARC Plus Touch remote control units, we designed a system that will play audio from the USB stick when both STL paths are silent for two minutes. Then, when normal audio is restored for a solid two minutes, it will revert back to it.

This is great for dire emergencies like the STL equipment being down or the studio generator not coming on during a power outage. However, for events like audio problems in the studio, when we have operators on hand, two minutes is an eternity!

So we wanted to give the operators a way to do the same thing we had at the transmitter site, but this time in the studio.

Dedicated fader

To achieve this, we added USB thumb drive players in the studio. We again put emergency audio on thumb drives and these were attached to the players by chains so they wouldn’t be lost.

While this was a better plan than CDs that would get lost in the studio, we still found operators not remembering in an emergency where to locate the drives, how to get the fader on the board changed to the player, and how to get it on the air. By the time this all took place, the two minutes were up, and the transmitter site player was already on the air.

I knew that the WheatNet-IP blades offered internal audio players, but we were still in a mixed infrastructure with the control rooms still having G5 Wheatstone control surfaces connected to the legacy TDM system. We also had some WheatNet-IP blade infrastructure with interconnections to the TDM system.

Still, it was going to be an issue for the operators to use the internal players if they had to dial up a fader on the old G5 surfaces

We went through our studio rebuild this past year and now have an entirely WheatNet-IP infrastructure. With that, we are now using the LXE control surfaces, which also took us from 16 faders to 20 faders. This allowed me to have a dedicated fader just for an emergency audio source.

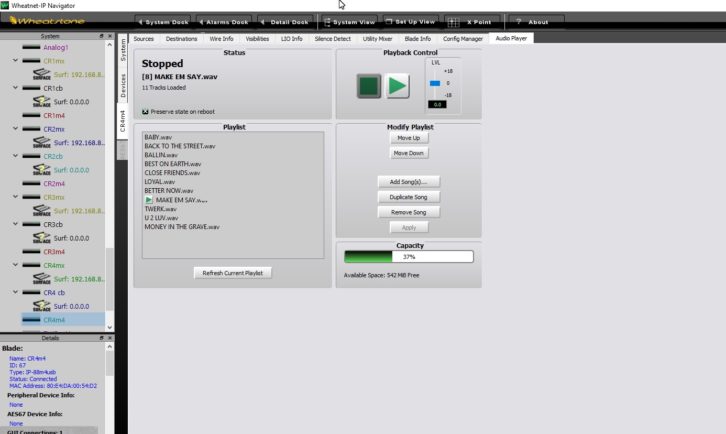

We purchased four licenses, one for each station, and activated the Audio Player tab on each of the M4 microphone processing blades in the control rooms.

We then assigned them to the very last fader on each of the LXE control surfaces.

Now here’s the catch: We wanted to make things as easy as possible — to have an emergency audio source that the operators could get on the air with one button. This means we had to make it difficult for the operators to change the fader to any other audio source.

One cool thing about the LXE control surfaces is that they are very programmable. Just about every button on the surface can be customized to the need.

Well, the first thing I did after assigning the emergency audio player to Fader 20 was to defeat the source select knob to remove the ability to change to the source at all on that channel. I also programmed the soft key to only select the emergency audio player.

I then took the program bus select button on the channel and made it into a tally-only button, showing that the fader is in program. Hitting the button does nothing to turn the fader program on or off. I instead used the second soft key button to be the program assign button on the fader.

The idea is that this fader is always in program and can’t be easily taken out of program without special knowledge. We still have conscientious operators who turn the program bus assignment off on what they deem unnecessary faders at the beginning of their shift, a practice that you usually only find with our very experienced operators but is not desired in this instance.

I, of course, enabled all the necessary steps so the player is remote started. The result is that the operators have an emergency audio source that only takes two steps: Turn up the fader and push the “on” button.

In my mind, this should mean that anything more than 10 seconds of silence is unacceptable. If the main audio source stops playing, that first instinct should be to immediately press that “on” button and then call engineering.

This article originally appeared in the Local Oscillator newsletter of Crawford Broadcasting.

Rick Sewell, CSRE, CBNT, AMD is engineering manager for Crawford Broadcasting–Chicago. Radio World welcomes tech tips and story ideas at [email protected].