Internet audio streaming and on-demand playback have become ubiquitous, both in consumer media and professional audio applications. Today, it is a $10 billion industry.

Despite this popularity, the effects of excessive loudness or inconsistent loudness between sources continue to detract from the listening experience. This topic was the subject of a presentation at a recent AES seminar by John Kean, former NPR senior technologist, moderated by David Bialik of David K. Bialik & Associates.

It discussed a new AES technical document on loudness guidelines, TD1008. Kean’s presentation was followed by a panel discussion among several members of the Drafting Group.

What’s LUFS?

To measure and control loudness, engineers speak in terms of LUFS, or Loudness Units relative to Full Scale, as defined by the ITU-R BS.1770-4 Loudness Meter standard.

LUFS relates loudness units to the maximum level that a system can handle, which is always expressed as a negative number, i.e., –18 LUFS. The less negative the number, the higher the average level. An increasing number of pro audio devices and software are equipped with LUFS metering.

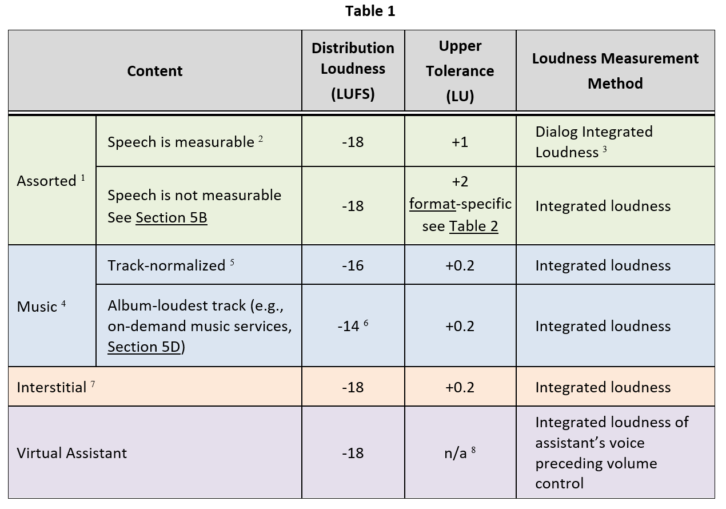

Table 1 of the TD1008 recommendations covers all audio distributed by streams and podcasts as well as on-demand music services. These include audio content that is either mixed speech and music, or all music, interstitials (e.g., advertisements) and even automated voice announcements. Content where speech is measurable serves as the –18 LUFS anchor, against which music, sound effects, etc. are mixed.

As discussed below, the document recommends that music content be album-normalized, if practical, or track-normalized to no more than –16 LUFS.

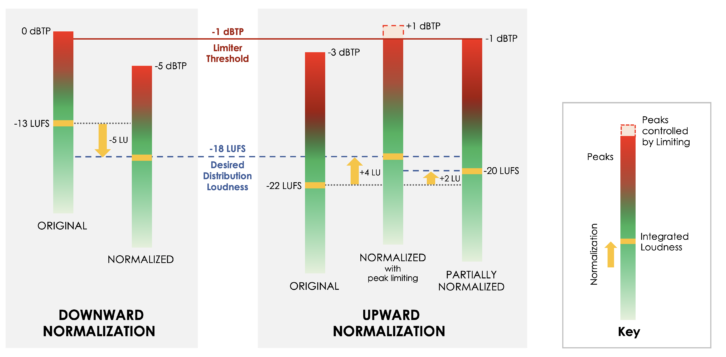

To reach the desired loudness, audio content is normalized in a downward direction if the content loudness is above the target loudness, or upward if it is below the target. The loudness of nearly all popular music is high, so only a downward gain is needed, requiring no further processing and effect on dynamics. There may be exceptions with upward normalization, such as content with a large peak-to-loudness ratio. Here, peak limiting may be best, or, if dynamic quality is affected, partial normalization may be necessary.

Music content is normalized for distribution in one of two ways. The first is “album normalization,” which preserves the relative loudness between songs on an album. This is preferred because it respects the artist’s intent for the way their music should sound. This technique is well-suited to on-demand or continuous music services.

Album normalization first measures the integrated loudness of each track on an album. The loudest track is then set to a loudness of –14 LUFS. The same amount of gain adjustment, up or down, is done to the remaining tracks of the album. The document notes that most popular music albums have loudness variation between songs of 2 to 3 LUFS.

Album normalization may be impractical in a radio-style production where songs are played out sequentially. In these cases, tracks are adjusted individually or “track normalized”: Each song or audio element is raised or lowered by different amounts to a similar loudness. However, this alters the artist’s intent by making some tracks sound louder or softer than they were intended.

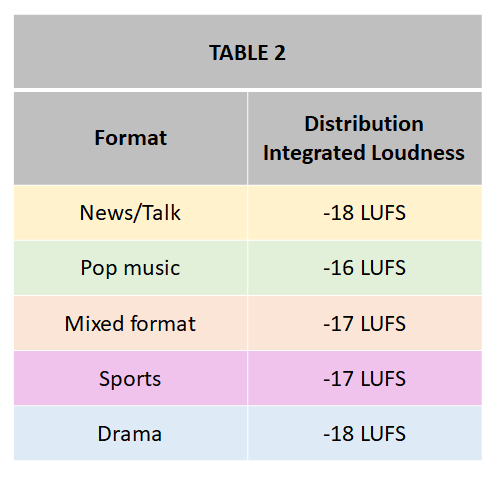

Table 2 in TD1008 provides simplified guidance on distribution loudness of track normalized content. News/talk and dramatic content is recommended at –18 LUFS, and popular music (track normalized) is recommended at –16 LUFS, which compensates for how the ITU Loudness Meter responds to voice and music. Mixed-format content and sports are targeted in the middle, at –17 LUFS. (These small differences require long-term measurement for accuracy.)

Distributors need to sensitively balance the requirements of listening environments against the aesthetic quality of their content. While fine arts programming may require reduced Integrated Loudness to help preserve the natural dynamics of a performance, popular music content requires no further processing, other than normalization.

Meaningful metadata

Audio metadata that is embedded in the stream will play an increasing role in managing loudness. Development is in progress on the production, distribution and playback device fronts, but may require several more years for full adoption.

When metadata is used, the original content is distributed to the player non-destructively. Listeners receive the same content, but the players use that metadata to manage the loudness and dynamics of the audio according to the noise environment, capabilities of the playback device and listeners’ needs.

Most new mobile devices and HTML5-compatible browsers can use audio metadata. Over time, newer devices with these features will replace legacy devices.

Techniques for audio metadata have been fully established in video services. Within a few years, audio services and devices will adopt this technology and can converge with video standards. Until metadata content is widely available, TD1008 recommends loudness procedures that are well-suited to current fixed and mobile listening.

Why it matters

There are benefits to broadcasters in following the TD1008 guidelines. Listeners will no longer need to readjust the volume from source to source, a long-standing annoyance. The guidelines help to preserve the artistic intent of the content, which may encourage longer listening.

One question that is being raised is whether –16 or –18 LUFS will be loud enough for listeners. The seminar participants agreed that the AES recommendations consider the many limitations in gain and acoustic output of consumer devices to ensure that most smart speakers, car audio systems and mobile devices will perform well.

Nearly all commercial music content requires no further processing (other than normalization) to meet these guidelines. In high-noise environments headphones are a much better option than trying to raise distribution loudness by excessive audio processing.

Complying with the guidelines is easier than it might first appear; –18 LUFS for speech-oriented programming and –16 LUFS for track-normalized music programming can be achieved with a simple audio processor. For best perceptual balance with mixed content, some radio-style audio processors of high quality are capable of handling the speech and music targets intrinsically (check with your manufacturer, or do your own listening tests).

The entire TD1008 document may be read online and downloaded from the AES website.

The AES Technical Committee for Broadcast and Online Delivery is developing a website about audio loudness that will be open to the public. The website will educate and demonstrate loudness techniques for audio distribution and content creation.