A recent article by Hans Johnson about “Robert Williams’ Odyssey in Cuba” brought back fond memories of listening to the AM band during those cold winter nights in New Jersey.

In 1966, my uncle gave me a non-working 1949 Delco table radio with a “magic eye” tuning indicator. I repaired the radio and set it on a bookshelf in my bedroom.

Much of that listening was mundane. I loved the hits on “Radio 8 CKLW,” WKBW in Buffalo, N.Y., or WLS and WCFL in Chicago, often hearing music that was not played on top 40 radio in New York or Philadelphia. These were the days before sterile, homogenized playlists. If I wanted to relax, I would tune to WGN for the Talman Federal Savings program, which featured soothing music. Canada’s CBC would offer a wide variety of programs, including “CBC Stage,” a series of original radio dramas. A real challenge was picking an intelligible signal out of the “cocktail party” on the Class IV channels.

A Cuban man holds an old radio in Havana in 2011. Radio has long been a tool used by the governments of Cuba and the United States in their international standoff. Photo credit: iStockphoto/Maria Pavlova

I soon discovered the radio war between the United States and Cuba.

SWAN ISLAND

In the 1960s, only two U.S. stations operated on 1160 kHz at night: KSL in Salt Lake City and WJJD in Chicago. To protect KSL, WJJD had to sign off at local sunset in Salt Lake City. But in New Jersey, I found a Spanish-language station with a strong signal on 1160. It was Radio Americas, which operated from Swan Island in the southern Caribbean.

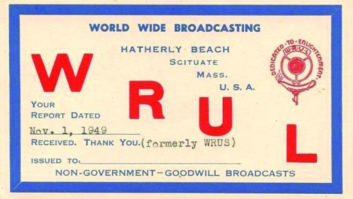

Swan Island was claimed jointly by the United States and Honduras. It had a weather station and was a refueling stop for fishing boats. Radio Americas operated on 1160 kHz with 50 kW into a three-tower array beamed north and on shortwave at 6000 kHz with 7 kW. Programming consisted of music, news and commentary. The sign-off announcement was done in both Spanish and English. A reception report addressed simply to “Radio Americas, Swan Island, West Indies” brought a yellowing QSL card in an envelope with a Miami post office box return address. (I still have that QSL card.)

Some months later, the now-defunct Popular Electronics magazine ran an article about the station, mentioning a possible CIA connection. The article even featured a rate card, although I never heard any commercials on Radio Americas. At my New Jersey location, the 1160 kHz outlet always had a better signal than the shortwave outlet.

In 1971, the United States ceded Swan Island to Honduras and Radio Americas fell silent.

‘LIBERACION’

Tuning the low end of the band yielded several powerful stations from Cuba.

Radio Rebelde held down 590 kHz from a transmitter in the Regla section of Havana. Programming was mass appeal, with music and a lot of winter baseball. On 640, I could hear Radio Liberación, the former CMQ, with a similar format to Radio Rebelde. CMBC, the station that aired “Radio Free Dixie,” could rarely be heard at my location, as CBF, key station of the French-language network of the CBC in Montreal, ran 50 kW there and the crude antenna that I used did not allow me to null out the Canadian signal.

At midnight Eastern time, the domestic services on 590 and 640 would sign off with the playing of the Cuban national anthem and a chimes interval signal would be heard for a minute or two. That was followed by a special all-night external service called “La Voz de Cuba” (“The Voice of Cuba”), which was the same programming that aired on shortwave via RHC.

By the mid-1980s, Radio Americas was long gone, but the radio war across the Strait of Florida heated up. In Miami, the longtime occupant of 710 kHz was WGBS, which carried an adult standards format in English. At night, WGBS beamed south to protect co-channel WOR in New York. In 1985, WGBS was purchased by Cuban immigrants. The format was changed to news/talk in Spanish and the call letters became WAQI. WAQI could be heard quite well in Havana.

One of its commentators was Juanita Castro…yes, Fidel’s sister. She detested communism and came to Miami in the 1960s. The Castro regime was livid over her broadcasts and the powerful Regla transmitter was retuned from 590 to 710. Other transmitters on the island were also set up on that frequency and all of them carry Radio Rebelde. There is collateral damage in that war: WOR still receives severe nighttime interference from Cuba, especially during the winter months.

RETALIATION

When the U.S. government put TV Martí on the air, the Cubans quickly retaliated. An extremely powerful transmitter, believed to be near Havana, was set up on 830 kHz. Although the modulation was weak, the carrier strength was comparable to that of a local station. Programming was in English under the name “Tour Radio” and the station’s accented announcers promoted tourism in Cuba. WCCO in Minneapolis, the dominant U.S. station on 830, reported interference in the suburbs of the Twin Cities.

I have not heard that station on 830 in a long time, although its Spanish-language version, Radio Taino, operates on 1180 kHz to jam Radio Martí. I can sometimes hear it under WHAM (Rochester, N.Y.) here in northeastern Pennsylvania. The programming ostensibly is intended for foreign tourists in Cuba and may include segments in English or other languages.

The Cubans still have a strong presence on the nighttime AM band. Radio Reloj (“Radio Clock”) has a strong signal on 570 kHz and other frequencies. Programming consists of two announcers alternating the reading of news copy over a background of 1 second time ticks. On the minute, the announcer says “Radio Reloj,” a time tone sounds, the announcer gives a time check, and a sounder consisting of the letters “RR” in Morse code is played. Sometimes, chimes that sound like a doorbell are substituted for the “RR” sounder. I do not know the significance of that.

Radio Musical Nacional can be heard on 590 with classical music, while Radio Rebelde blasts in on 600, 670 and 710. Radio Progreso (the domestic service formerly heard in Havana on 690) can be heard on 640 and 890 (where it often overrides WLS). Programming consists mostly of popular music, with children’s programs in the early evening. Since these are domestic services, all of this programming is in Spanish.

The author is a former chief engineer of stations in Wilkes-Barre, Pa.