The author is senior solutions consultant for The Telos Alliance

Most of radio’s operational systems can now be “virtualized” or soon will be capable of it. The implications for broadcasters will be either minimal or staggering, depending on each broadcaster’s business and operational models in the future.

The transition to virtualization — the first form of it — actually began in the late 1980s with simple PC-based automation systems replacing tape cart machines. Long gone are squeaky pinch rollers, worn tape heads and lubricated tape sliding against itself in endless loops. And while the transition to all-digital storage and playback took nearly two decades, we learned a lot along the way. Just as other industries have demanded, and now use, better computing hardware and more reliable operating systems, radio broadcasting benefits from the same improving technology as other business-tech sectors.

TRANSITION

Are computers perfect replacements for the purpose-built equipment we’ve come to romanticize? Hardly. Yet despite their shortcomings, PCs have proven to offer better overall usability, reliability and audio quality than the cart machines, reel-to-reel decks and turntables they replaced. And today’s PC-based playout systems are even better than the CD players — and their audio skipping — of the 1980s and 90s.

Over the past 20-plus years, we’ve “virtualized” the operation of many devices that were previously “purpose-built.” And while PCs proliferated throughout broadcast facilities, some vexing problems attended the PC takeover.

The life cycles of hard drives, cooling fans and power supplies conspire to bring regular failures to any facility that depends upon dozens of PCs for continuous operation. Seems we’ve replaced purpose-built audio equipment with PCs performing specific duties, and our device count may not have changed much from our older scenarios.

Tech businesses in other sectors have had similar challenges. Many of these challenges have been addressed using far more robust computing platforms than PCs. “Server-grade” hardware — including motherboards, CPUs, cooling fans, hard drives and power supplies — provide a level of performance and reliability not found in PC-grade systems. But server-grade hardware is expensive — too expensive for many broadcasters to replace their consumer PCs with a similar number of server-grade computers.

This price point is where computer virtualization raises its hand to say, “Hey, I have your solution right here!” That solution involves virtualizing those very systems even further by moving their functions out of numerous dedicated PCs and into a server-grade platform, plus a full backup.

These servers run multiple virtual “PCs” internally — anywhere from two or three systems up to several dozen. Some broadcasters began shifting their internal business processes onto multi-platform servers as far back as 10 years ago. But moving real-time audio processes to virtualization servers is just now gaining interest.

One early experimenter — and then early adopter — has been BBC Local Radio. The BBC operates “local” radio stations in about 40 cities across England.

EXPANSION

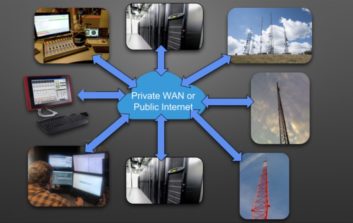

In 2014 the BBC embarked on a quest to reduce the difficulties and expenses associated with local equipment capital and maintenance costs, as well as a shortage of engineers to refit 80 complex studios. The result is “ViLoR,” short for Virtual Local Radio. The local studios operate about the same as with the old, legacy equipment, but the underlying broadcast infrastructure lives within two data centers in London and Birmingham. Automation playout, talk show systems, audio codecs and even live on-air audio mixing are handled at the data centers by high-reliability servers. Redundant data connections and dual studios / data centers assure six 9’s of uptime.

The BBC is using resources more efficiently than before in terms of capital costs, maintenance and monthly expenses such as HVAC. The new ViLoR system maintains audio in digital perfection with extreme ease-of-use for the on-air talent. Serendipitously, ViLoR affords a renewed emphasis on talent, content creation and effective multi-platform distribution.

Recent developments are bringing broadcast infrastructure virtualization to more broadcasters — even those without large budgets. Since “virtualization” embodies several definitions and manifestations, broadcasters can virtualize a few things now, then move toward radical virtualization of their infrastructure when the time is right.

[Read: New Broadcast Console From Axia Audio]

A contemporary example of virtualization is moving the audio console surface plus phone interaction and other studio controls to a touchscreen. Today’s multi-touch screens offer effortless and accurate control, and the layouts are customizable for each show or on-air talent. They can be less expensive than the traditional controls they replace.

Another form of virtualization is to move automation playout systems onto Virtual Machines (“VMs”) running on powerful, server-grade platforms. Some automation manufacturers are supporting this scenario already, and most are planning on it.

At Delta Radio in Mississippi, hardened servers are running five instances of the Rivendell automation system. Audio and GPIO signalling is done entirely in Livewire audio over IP, so no sound cards or GPIO cards are needed at the server. The server offers four 1 Gbps Ethernet connections, of which only two are used — one for the Livewire AoIP network and the other for VNC access, audio and log file transfers, and other command/control functions. Once set up and tested, these automation systems have worked flawlessly. Two of the stations are entirely automated while three have some local, live-assist shifts.

All of these stations ingest voice-tracking files daily, as well as some long-form programs, hourly weather forecasts and daily local news files. Actually, the automation systems running in VMs all share a Network Attached Storage (“NAS”) server. Ingest and formatting of new audio isn’t duplicated by each station; rather it’s done once by another VM running an automated ingest and quality-control application called WebGopher. This application has freed up our local talent from the tedium of manually dubbing the hundreds of audio cuts that are updated daily. Now they can focus on their shows, voice-tracking and doing frequent remote broadcasts from local events and advertisers.

A further virtualization scenario appears when we replace audio mixing hardware (dedicated console “engines”) with audio mixing engines running on PCs — or better yet, on VMs. Audio over IP technology is making this quite doable. As mentioned, the BBC began such operation nearly five years ago. When mixing engines are virtualized, radio studios may have simple audio mixing control surfaces, along with mics, headphones, touchscreens and button panels; the heavy lifting of the rest of our typical infrastructure will all be virtualized in clean, safe data centers, either on-site or in a secure off-site facility. Webcasters are already operating some of their facilities entirely in the cloud. The features and functions that broadcasters need are being developed now.

Will virtualized broadcast infrastructure be better, more reliable, cost less? Will it allow talent to focus more on their craft — and do that from anywhere? Stay tuned. The future does look virtual, and that’s a reality we’ll have to deal with.