In radio’s formative years, most stations were only on the air for several hours in the evening, and the majority of what they broadcast was music. There were a few stations that provided news headlines and sports scores, but listeners did not expect breaking news coverage, nor live play-by-play broadcasts of their favorite teams.

Throughout the early 1920s, as the programming day gradually expanded, so did what was on the air. By the mid-1920s, radio was covering important news events, and many stations began broadcasting major league baseball games, much to the delight of the fans.

But there was one group of fans whose favorite teams never got on the air. If you followed the Chicago American Giants, the Kansas City Monarchs, the Indianapolis ABCs or the other teams in the Negro Leagues, radio ignored you.

In fact, the only way to find out how your team did was to either go to the game or read about it in the Black press. Because America was segregated, it was mainly sportswriters at Black newspapers like the Chicago Defender, Pittsburgh Courier, and Baltimore Afro-American that offered extensive coverage of Negro Leagues teams.

Jocko

No matter how well-attended Negro Leagues games were or how much talent the players displayed, radio stations weren’t interested.

Perhaps that wasn’t surprising: In the 1920s, all station owners were white, and they seemed convinced that white listeners wouldn’t care about Negro Leagues baseball — even though newspaper accounts noted that many white people went to the games.

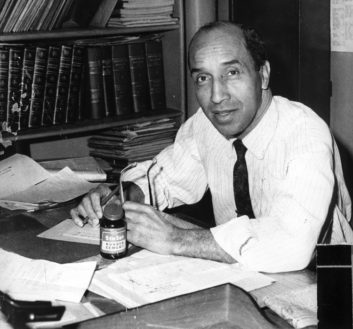

It wasn’t until late 1929 or early 1930 (the exact date is uncertain) when the first Black sportscaster went on the air: Sherman “Jocko” Maxwell was a former semipro baseball player and manager from Newark, N.J. He debuted a five-minute radio show on WNJ (later WNJR) in Newark.

At first, he mainly read sports headlines, but his show went over well with local fans and by 1932, Maxwell was hosting a 15-minute program. By 1933, he was on the air in New York City at WRNY, and then at WHOM, where he hosted his increasingly popular sports show several nights a week.

By 1937, Maxwell was on the air at WWRL, where he was named the station’s sports director in 1942 — the only Black sports director in radio at that time.

Maxwell had an audience of both Black and white listeners, and he had so much credibility that Major League players would often stop by his show for a chat.

He was also a correspondent for the Sporting News, and during the 1930s, he covered some of the Newark Eagles’ Negro Leagues games. This gave him an opportunity to discuss the games on his radio shows, where he sometimes compared certain Black players to their major league counterparts, something most other sports commentators were not doing.

Meanwhile, in Washington, D.C., another Black sportscaster went on the air in the mid-1930s.

Sam Lacy was already a sportswriter for the Washington Tribune who would go on to have a long career with the Baltimore Afro-American.

In the autumn of 1935, he began doing a sports show for WOL. Like Jocko Maxwell, Lacy was a big fan of the Negro Leagues, and both men had served as public address announcers at their team’s ballparks.

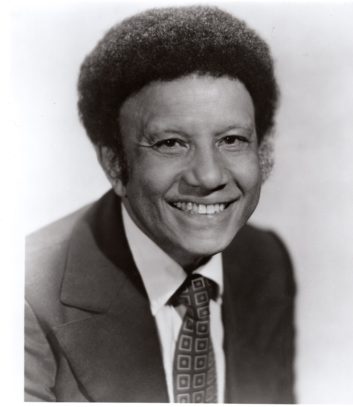

After Lacy returned to his sportswriting job, he mentored a young man named Harold Jackson, later better known as Hal Jackson and a major force in Black radio.

Jackson wanted to be a sportscaster, but no station owner in the D.C. area would hire him. He finally got on the air in 1939 at WINX, hosting a music and interview program, and thanks to Lacy, he also was hired as the public address announcer for the Homestead Grays games at Washington’s Griffith Stadium.

Grays vs. Elite Giants

But it wasn’t until Aug. 9, 1942, 22 years after the Negro Leagues had been founded, that the first play-by-play broadcasts of Negro Leagues games finally occurred, with Jackson as one of the announcers.

Sponsored by the Baltimore Afro-American, Washington station WWDC broadcast the series featuring the Homestead Grays and the Baltimore Elite Giants. WWDC also agreed to broadcast several other Homestead Grays games, including one against the Kansas City Monarchs in September.

No Negro Leagues games seem to have been broadcast during the next several years. Meanwhile, Sam Lacy and Harold Jackson collaborated on a once-weekly sports show on WINX in 1944, during which they interviewed Negro Leagues players and recapped the games from that week.

Contrary to some internet claims, there is little evidence of any regular play-by-play broadcasts until 1948, when the Cleveland Buckeyes got on the air at station WSRS; the station’s sportscaster Danny Landau did the play-by-play, assisted by sportswriter A.S. “Doc” Young, who covered the Negro Leagues for the Cleveland Call and Post.

But an effort to broadcast the Atlanta Black Crackers games over WEAS in Decatur, Georgia in mid-May 1948 was not as well-received: After one game between the Black Crackers and the Nashville Cubs got on the air, a subsequent broadcast had to be canceled after complaints from what one Black newspaper referred to as “Southern bigots.”

Ironically, by the time more games were about to be broadcast, the Negro Leagues were in decline. Major League Baseball had finally begun to integrate in 1947 with the arrival of Jackie Robinson, and soon, there were questions about whether the Negro Leagues would survive.

The Negro National League disbanded in 1948; the Negro American League struggled on, in weakened form, through the 1950s.

As a media historian and a baseball fan, I am saddened that most radio stations ignored the Negro Leagues when they were at their best. Because so few stations broadcast any of their games — and not until the 1940s — baseball fans were deprived of the chance to follow the exploits of talented (and record-breaking) 1930s players like slugger Josh Gibson and speedster “Cool Papa” Bell or hear about how pitcher Satchel Paige’s legendary career developed.

It was a loss for the fans. But it was a missed opportunity for radio.