We conclude our series about the early days of broadcasting before and around the famous KDKA broadcast 100 years ago. See other recent articles in the Radio @100 series.

In any important endeavor there seems to be a certain amount of contention as to who was really “first.”

In aviation, the Wright’s supremacy in making the first powered flight has been challenged by supporters of Clément Ader, Hiram Maxim, Gustave Whitehead and Richard Pearse. There are those who argue that Elisha Gray or Antonio Meucci should be given credit for inventing the telephone.

In broadcasting, there are serious contenders for the history book position of being the “world’s first radio broadcaster,” including one that aired election returns at the same time KDKA held its inaugural Nov. 2, 1920 broadcast.

As mentioned in our earlier account of the KDKA broadcast, there seems to be some agreement on what constitutes a broadcast service. At a minimum, these include (1) programming intended for the general public, (2) the advertising of transmissions in advance and (3) a regular pattern of broadcasts.

Earlier “broadcasts” by Fessenden, de Forest and Herrold easily fall outside of these criteria.

SHOULD “MARCONI” GET THE PRIZE?

Interestingly, a British effort, initiated by Marconi employees no less, comes very close to passing the litmus test and certainly antedates the KDKA “big broadcast.”

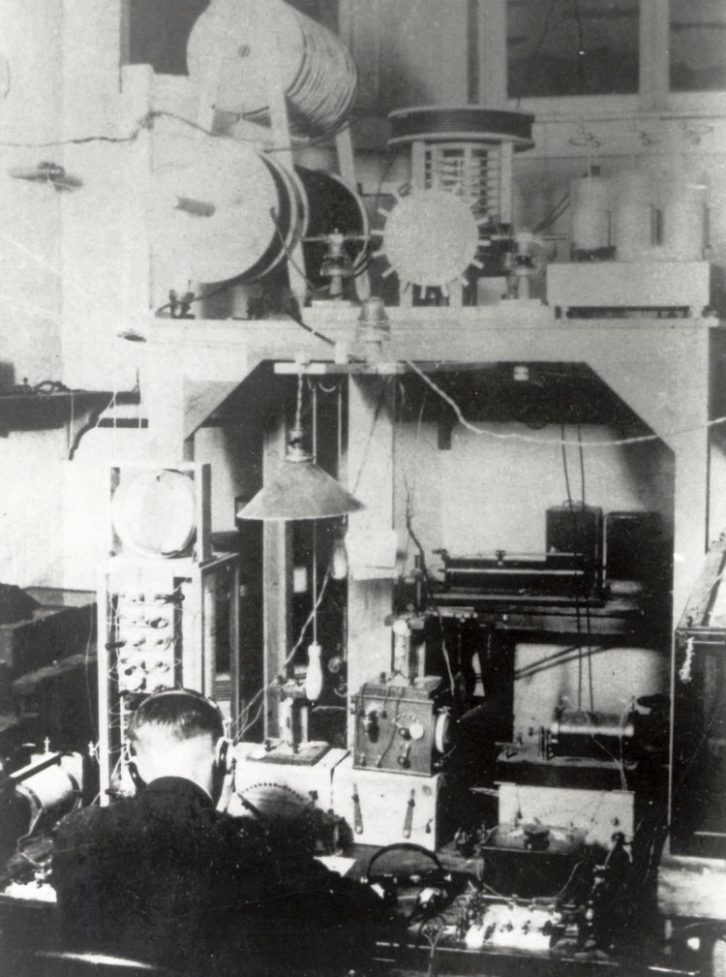

This was the establishment in December 1919 of 6 kW experimental radiotelephone station MZX at the large Marconi manufacturing facility in Chelmsford, England.

Documentation reveals that broadcasts of a sort began there on Jan. 15, 1920, with regular programs of speech and phonograph records. More than 200 reports of reception were received from amateur and shipboard radio operators. The station initially could be heard from Norway to Portugal, with one report coming from a listener 1,450 miles distant. Power was soon upped (15 kW input) and a regular schedule of two transmissions per day was established in late February with the airing of newscasts.

Following this round of testing, MZX added “readings from newspapers, gramophone records, and … live musical performers,” as Tim Wander writes in “2MT Writtle: The Story of British Broadcasting.”

A still-extant telegram offers testimony that on March 20, 1920 the station’s offerings were heard as far away as Australia. “Listening in” was not confined to “hams” and commercial operators, either.

Newspapers began to take notice, and one, London’s Daily Mail, decided to make a broadcasting “splash” in a really big way by footing the bill for an international superstar of that era, opera soprano Dame Nellie Melba, to perform live at the fledgling station.

Melba (in whose honor “Peach Melba” and “Melba Toast” are said to have been created) was paid the huge sum of £1,000 — the buying power of about $50,000 today — for a 20-minute performance on the evening of June 15, 1920. Obviously, the newspaper believed there was a future in broadcasting.

The Mail gave its “big broadcast” quite a buildup, with the British government issuing almost 600 new receiver licenses during the two-month runup. It was a truly international broadcast too, being heard in countries all over Europe, even as far away as New York. (A loudspeaker arrangement was deployed in Paris so people in the streets could hear Melba perform.)

So, with success spelled in such numbers (listeners and talent fee alike), why shouldn’t MZX get the honors for being the premier broadcaster?

It boils down to lack of sustainability. Following a complaint made five months after the Melba musicale to the House of Commons by the Postmaster General about MZX’s operations interfering with “legitimate services,” the station was ordered closed.

As Wander put it in his book, “This view seemed to be echoed by the Navy and Army, who stoutly maintained that any civilian broadcasting would hamper ‘genuine experiments’ and would not be in the best interests of imperial defense. The critics of wireless broadcasting saw that the device was ideally equipped to be a servant of mankind, but were determined that it should never be considered as a toy to amuse children.”

DO DITS AND DAHS COUNT?

On the U.S. side of the pond, KDKA had contenders also.

One frequently mentioned is the University of Wisconsin’s 9XM, now WHA. It was licensed initially for experimental transmissions in June 1915 and, following the lead of similar stations at other schools, soon began a regular schedule of transmitting weather reports for the benefit of farmers and others. The rub: these were via radiotelegraphy, and those who wanted to benefit had to learn Morse code.

A couple of years into these daily code broadcasts, the station experimented with radiotelephony, broadcasting phonograph records and live announcements just as Conrad did at his ham station.

Progress was slowed by the World War but resumed in early 1920 with a relicensing of the station, which had been engaged in research for the military.

Radiotelephone broadcasts of the regular weather reports were promised but did not become a reality, continuing in code instead. As noted in his 2006 history “9XM Talking: WHA Radio and the Wisconsin Idea,” Randall Davidson wrote: “On November 2, the evening that KDKA made its debut broadcast with results of the Harding-Cox election, 9XM may also have been on the air, albeit only telegraphically.”

These code-only transmissions went on into until early 1921, with only sporadic attempts to transmit speech and music — too late to best KDKA in meeting the criterion of “being accessible by the general public.”

WHY NOT DETROIT?

Perhaps the greatest challenge to KDKA’s “first and foremost” status was Detroit’s 8MK (later WBL, and now WWJ), which was owned by The Detroit News.

It commenced radiotelephone transmissions on Aug. 20, 1920 of news on a daily basis, more than two months before KDKA took to the air. Adding to the station’s claim for priority was information printed in the News instructing readers as to how they could take advantage of this wireless service.

There was a slight problem, however. 8MK was licensed as an amateur station and could operate only on wavelengths reserved for amateur use, in this case 200 meters (about 1500 kHz), and as such was subject to interference from ham operators. (KDKA had requested and obtained a commercial license from the Department of Commerce, which allowed operation on a lower frequency well separated from amateur transmissions.)

And to further handicap matters, the de Forest “radiophone” transmitter leased by the News operated at one-fifth the power employed at KDKA.

8MK initiated a rather serious broadcasting agenda beginning on Aug. 20 with reporting of returns from an election held on that date, and continued with daily transmissions of news reports interspersed with music. Records show that the station was on the air the night of Nov. 2, 1920 with a pre-announced broadcast of election returns, just as KDKA was doing some 200 miles away,

So why shouldn’t this fledgling broadcaster get the honors for being first? They were on the air well in advance of KDKA, advertised their broadcasts in advance and continued on a regular schedule after the election eve reporting. (The station was licensed for limited commercial operation in late 1921 and received the call sign WBL. This was changed to WWJ the following year.)

Perhaps broadcast historians Chris Sterling and John Kittross explain it best in “Stay Tuned: A History of American Broadcasting,” where they write:

“While it isn’t easy to compare and adjudicate such conflicting claims, it can be done. As to broadcasting licenses, KDKA led WBL (WWJ) by nearly a year. Conrad’s amateur station, 8XK, successor to the prewar station, went on the air more than a year before 8MK and was broadcasting music 10 months earlier. As to license holding, Westinghouse or one of its officers held a license before the Detroit News did. Only by maintaining that 8XK is not the precursor of KDKA, and that 8MK is the precursor of WWJ, can one uphold WWJ’s claim — and both Conrad’s status as a Westinghouse employee and the Detroit News’ delay in applying for a broadcasting license belie that position.”

Doubtless, other claims could be made for supremacy in terms of “who was really on first.” However, as the old saying goes, “close” only counts in the game of horseshoes.

The author thanks Mark Schubin for his assistance with the Dame Nellie Melba photo and information, and broadcast historian and author Tim Wander for information about the 1920 Marconi Melba broadcast. Wander has published a limited edition 270-page book “From Marconi to Melba, The Centenary of British Radio Broadcasting,” which details the beginnings of radio broadcasting in the U.K.