A document written on Capitol Hill recently merits more attention that it has received.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office submitted the report to a House subcommittee in September. The topic was public alert and warning.

As most RW readers know, FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, is responsible for the Emergency Alert System and for developing a new Integrated Public Alert and Warning System, or IPAWS, which will supersede EAS and constitute the nation’s public alert system.

The GAO examined the status of EAS, progress in implementing the new system and challenges involved. It surveyed emergency management directors and talked with officials of FEMA, DHS and NOAA, as well as other participants and “stakeholders” like alerting companies and consumer groups.

Blunt

I found much of language in the report surprisingly succinct, unlike much of what comes out of the Washington bureaucracy.

“As the primary national-level public warning system, EAS is an important alert tool, but it exhibits longstanding weaknesses that limit its effectiveness,” the authors wrote in the summary.

“EAS allows state and local officials limited ability to produce public alerts via television and radio. Weaknesses with EAS include lack of reliability of the message distribution system; gaps in coverage; insufficient testing; and inadequate training of personnel.

“Further, EAS provides little capability to alert specific geographic areas. EAS does not ensure message delivery for individuals with hearing and vision disabilities, and non-English speakers.”

These weaknesses aren’t new, of course, and GAO noted that FEMA does have projects to address some of them.

The GAO report included examples of incomplete IPAWS projects with missed timelines. “However, to date, little progress has been made and EAS remains largely unchanged since GAO’s previous review, completed in March 2007. As a result, EAS does not fulfill the need for a reliable, comprehensive alert system,” the authors continued.

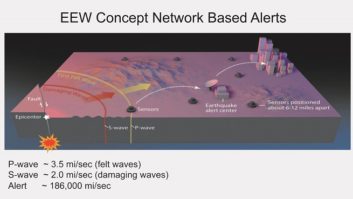

They pointed out that the IPAWS program, conceived five years ago, aims to integrate new and existing alert capabilities, including EAS, into a comprehensive “system of systems.”

“However, national-level alert capabilities have remained unchanged and new technologies have not been adopted,” they found.

“IPAWS efforts have been affected by shifting program goals, lack of continuity in planning, staff turnover and poorly organized program information from which to make management decisions. The vision of IPAWS has changed twice over the course of the program and strategic goals and milestones are not clearly defined, as IPAWS operated without an implementation plan from early 2007 through June 2009.”

The result, they wrote, was that as state and local governments go about creating their own alert systems, “IPAWS program implementation has stalled and many of the functional goals of IPAWS, such as geo-targeting of messages and dissemination through redundant pathways to multiple devices, have yet to reach operational capacity.”

It said FEMA had done pilot projects without assessing outcomes or lessons learned and “without substantially advancing alert and warning systems.” It criticized FEMA for not periodically reporting on IPAWS progress.

The GAO continued by saying that although public warning depends on cooperation of people and organizations, “many stakeholders GAO contacted knew little about IPAWS and expressed the need for better coordination with FEMA. FEMA has taken steps to improve its coordination efforts, but the scope of stakeholder involvement is limited.

“FEMA also faces technical challenges related to systems integration, standards development, the development of geo-targeted and multilingual alerts, and alerts for individuals with disabilities.”

Limited progress

The authors concluded that FEMA had made limited progress in implementing this hoped-for comprehensive alert system.

“Management turnover, inadequate planning and a lack of stakeholder coordination have delayed implementation of IPAWS and left the nation dependent on an antiquated, unreliable national alert system. FEMA’s delays also appear to have made IPAWS implementation more difficult in the absence of federal leadership as states have forged ahead and invested in their own alert and warning systems.”

GAO laid out recommended steps for FEMA. These involve setting goals and milestones, prioritizing in consultation with everyone involved, reporting periodically to Congress and the secretary of Homeland Security, establishing a plan to verify the dependability of systems in use, and better training.

Also, with IPAWS years from full implementation, they reiterated that FEMA should work with the FCC on a plan to verify the dependability and effectiveness of the EAS relay distribution system, and said participants should have the training and technical skills to issue effective alerts. They also said that “a lack of training and national-level testing raises questions about whether the [EAS] relay system would actually work during a national-level emergency.”

The authors also said that the DHS had agreed with all of its suggestions and was acting on them. But GAO worried that “FEMA’s planned actions to address some of the recommendations might be insufficient.”

I don’t envy those who have to try to build an alerting infrastructure for the country. It’s a sprawling job with a sprawling list of people, companies and organizations, all with their own interests to push.

Further, this report’s sweeping conclusions may downplay meaningful progress. As RW reported in a story about EAS and IPAWS this summer, broadcasters recently have expressed renewed trust in FEMA and its efforts under recent management.

But for anyone familiar with EAS or interested in the challenges of creating an effective replacement, the GAO report is recommended reading. I hope government officials involved have already taken its findings to heart.

You can find the PDF at www.rwonline.com/uploadedFiles/Radio_World/GAO_emerPrep.pdf.