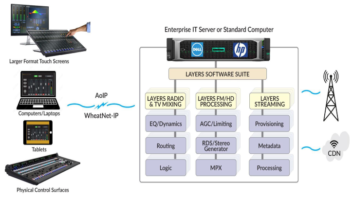

Wheatstone Corp., developer of the WheatNet IP audio network, has expanded into the cloud and server realm with its Layers Software Suite, which includes mixing, streaming and FM software hosted on a local server or running on cloud data centers.

At the NAB Show the company is adding Reliable Internet Stream Transport protocol to its AoIP technology and running its Layers software on Amazon Web Services Global Accelerator.

As part of Radio World’s series of manufacturer interviews about technology trends, Wheatstone’s Jay Tyler, director of sales, and John Davis, southwest tech engineer, sat down to talk with us ahead of the convention.

Radio World: Jay what is the most important evolution happening in radio studio technology?

Jay Tyler: Standardization. Radio consolidation meant companies buying stations, then getting everyone into one building and choosing a common traffic billing automation system and console routing system.

Companies obviously were looking to leverage their buying power; but today there also are fewer people available to make intelligent decisions in local markets or maintain equipment. Now we’re seeing even more integration between the automation, console routing, intercom and telephone systems, bringing another level of complexity.

We see standardization at big corporate clients like iHeartMedia. Townsquare has been rolling it out; Bonneville has completed it, Hubbard has mostly completed it. All the Entravision sites are WheatNet, the Cox media sites, a good amount of Saga. All of Beasley’s and Crawford’s stations have been completed.

RW: When you say “rolling it out,” you mean they’ve standardized on a Wheatstone AoIP infrastructure —

Tyler: And an automation system playout system.

RW: How well does this approach scale for a company that’s not one of the biggest groups?

Tyler: NRG Media has three dozen stations, for example, and it’s working for them.

Meanwhile, because there are fewer qualified engineers, some of these groups have created “tiger” teams who maintain this standardized gear and who travel a lot. Or they have named internal specialists as a resource. Or they’ve adopted a centralized NOC approach.

John Davis: Often, even if a group doesn’t have a team that travels and manages everything centrally, they’ve set up subject matter experts, one or two engineers in each market who know WheatNet, who know their chosen automation system or transmitter — an internal resource, someone you can reach out to who’s familiar with the way your company does things.

Tyler: Some have become quite self-supportive, almost independent of the manufacturers. For instance we rarely get service calls from Bonneville. In fact these groups will ask their engineers to turn first to their company’s internal resources when they need help.

RW: During and after COVID, we heard that buildouts would become more streamlined, with smaller footprints and more virtualization. A company might build one studio where they’d have built four in the past. Is that happening?

Tyler: Not on a grand scale. We still need multiple microphones. We have guests. We need a performance space.

Yes, bigger companies are doing some of this, an iHeart or a Cumulus. But for mid to large markets at companies such as Hubbard, Cox or Beasley, we’re still building a dedicated studio for every air signal; then there’s a backup air studio, and an adjacent production room for each studio.

In a market like Tampa they might have five brands, and they’ll still build five studios, including one as a backup or production. Whereas for iHeart, a market with five brands needs three control rooms — and a good schedule.

Davis: In smaller markets, a company might have four stations served by a main studio and a couple of auxiliaries. Sometimes the room is live only for four hours, at other times it serves as the production room. Instead of a dedicated studio plus production plus news, you end up with only as many studios as you have concurrent live dayparts; the rest of the time you’re in automation and using the space for production or recording commercials.

RW: To what extent has virtualization moved important infrastructure off-site?

Davis: It depends on the group. Some are starting to do a lot of remote tracking, especially where you have nationalized dayparts. One person will lay down a show for all the country stations in the company, then go back to the major stations and drop in two or three liners per daypart per hour that might be localized; the rest is network content.

Tyler: But with today’s technology, a group doing a “build in place” can streamline everything. We can drop one talk studio into a facility, surround it by four adjacent air rooms, and on any day at any time, one of those rooms can take control, with sight lines between them all.

Davis: I just worked on an installation for a public station that used a combination of Glass LXE and physical LXE panels in the same room. They had six or eight physical faders, then we put a big touchscreen in the middle for 20 or so more faders, and then another eight on the other side of the touch panel.

The first eight faders are for mics in the talk booth. The Glass LXE controls sources they don’t use every day, and the faders off to the side are what they need for the “Morning Edition” and “All Things Considered” dayparts. They streamlined that room for talk programming but can do simple production in the middle, and their tentpole dayparts are supported, all in one space. They’ll build their other rooms that way and have flexibility across the facility.

RW: To what extent do virtualization and the software-based air chain affect what you do?

Davis: It’s a lot easier to virtualize the back end of the air chain than the front, just because of latency. Our Layers Stream and Layers FM products handle processing and streaming in AWS after it’s left the studio, so I’m not worried about being able to put on a pair of headphones and hear myself with that delay. But until the latency issue gets resolved, you’ll see it more on the back end.

Tyler: It affects our design and development. Most engineers I’ve spoken with prefer the idea of virtualization with a local server — they still like being able to touch that server.

Our Layers FM, Layers Stream and Layers Mix are based on new technology that is easily ported over from a local server to containerization virtualization in a cloud, like AWS. We’ve just received a really nice order for Rogers Communications in Canada, which is creating a national streaming center using Layers Streaming. But again, these are local — an engineer can go put his hands on that equipment. I think engineers are winning that fight on the local level. They want to distribute their losses, they want multiple, on-premise servers.

But there are customers using cloud-based air chains. That’s what we designed Layers FM for. At the NAB Show we’ll demonstrate local mixing on the exhibit floor, sending it up to AWS, being processed in the cloud and then returned via AWS to the show floor so you can listen to an air chain that’s being virtualized.

You mentioned the endpoint. When we talk about low-latency linear streaming, we’re talking about well-connected sites, usually with multiple networks, main and backup, using big IP links. But a lot of transmitters in the field still have low-level connectivity. This is where boxes for MPX over IP come into play. Our SystemLink MPX over IP Transporter is for that endpoint. It’s an MPX over IP transporter that uses Reliable Internet Stream Transport, or RIST, so it can transport FM MPX over IP links of any capacity, whether as uncompressed or compressed.

Davis: With RIST you’ve got serial numbers on every packet. So we know if a packet is missing and can ask for a new transmission. You’re not just spitting out a bunch of UDP and hope that it gets to the end. With RIST, you know it got there. And it’s encrypted, so it’s secure. We also use RIST in our Blade-4 because it is such a robust transport protocol.

[Related: “What’s RIST and Why Do You Need It?”]

Tyler: Transmitter sites are getting smarter. There is a big movement for people to get off satellites and find different ways to deliver content over IP. If you can take syndicated shows along with programming from one station and programming from another station and consolidate it all in the cloud to distribute to transmitter sites over IP, then that becomes much more useful. This is the concept behind our Layers FM software, which puts the AGC, limiting and FM subcarriers in the cloud.

To complete the air chain in the cloud, you need one more critical piece: an MPX transporter like SystemLink for moving all that from the cloud directly to the transmitter site over any variety of IP links available to you. What’s really neat about SystemLink is that we align the FM and HD at the beginning, in the packets, so there’s no way for it ever to become unaligned.

RW: Where do you see it all going?

Tyler: As connectivity gets better, all of these transmitter sites are going to get more intelligent. Every Blade 4, our AoIP I/O unit, has the ability to stream; we have audio codecs in the Blade 4 so we can get audio from any site over the public internet directly to a transmitter site. That’s what our customers are asking for because they realize that they can bypass the studios in some cases, and they are fortifying these sites.

RW: Is this still a good time to be an audio equipment manufacturer?

Tyler: Yes. The convergence of IT and audio will continue. But you’ll still need to take a microphone and wire it to something; there still needs to be mixing and acquisition and distribution. It’s like any other business, with ups and downs. But radio isn’t going to go away.