FROM THE EDITOR

I am an ardent believer in efforts to save America’s radio heritage, including the work now being done by the Radio Preservation Task Force (http://radiopreservation.org). Here is the second in a series of occasional guest commentaries by or about those involved in the effort. Ken Freedman is general manager of WFMU (wfmu.org) in East Orange, N.J., the popular and longest-running freeform radio station in the United States.

— Paul McLane

It’s hard enough to describe the present, let alone predict the future. But at WFMU we keep bumping into the future, especially with regard to our digital archives.

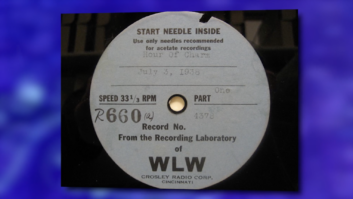

Most radio archivists focus on historic airchecks living on physical media such as reel and cassette tape, which means that the process of digitization becomes incredibly time-consuming and laborious, especially when adding metadata, tags and art. In comparison to that, digitizing media of the present is a cakewalk!

It always astonishes me that so little archival effort is put into preserving the present, when last I heard, the present instantaneously becomes the past. The easiest, cheapest way to preserve radio for the future is to focus on the present, and then deal with the past when you have more time and money. As if that ever happens.

WFMU’s record library.EVOLVING STORAGE MEDIA

We started archiving our airchecks digitally in 1997 and went whole hog in 2001, saving each and every radio show that we’ve broadcast and maintaining multiple backups. Unfortunately, when we first started archiving everything full-time, we did so using very low fidelity online streaming formats. Some of those formats have since fallen into obscurity, which has meant the laborious process of transcoding years of archives into more contemporary streaming formats.

But the good news is that storage gets cheaper and cheaper, and for the last few years we’ve saved our program archives as uncompressed FLAC files, as well as MP3 and MP4s. We’ve learned the hard way that with digital files, we have to back them up and recopy them from one machine to another, over and over again. The folks at the Library of Congress told me that they “refresh” their digital archives every two to three years. Doing this prevents the problem that I have with a handful of external drives from a mere six or seven years ago; they’ve been rendered obsolete and unplayable due to pesky hardware issues like outdated BIOS and unsupported operating systems.

Contrast that with good, old-fashioned reel-to-reel tape. I was contacted in 2001 by Tex, a former WFMU engineer, who had reel-to-reel airchecks of the station going back to 1961. Forty years later, Tex was able to copy of all these tapes to my format of choice — which was, unfortunately, DAT. No sooner did I receive a few boxes of DATs than I started plotting how to get them off of DAT and onto something with more longevity (like reel to reel tape?!).

WFMU signed on the air in 1958, and listeners and ex-staffers frequently contact me and offer up shoeboxes full of cassette, reel-to-reel and DAT airchecks. I accept them every time, no questions asked, and give them the place of honor I reserve for all historic tape archives: the climate-controlled crawl space located conveniently above the bathrooms. I like to pretend that someday we’ll have the money and manpower to convert all of these to digital. It’s fun to pretend. Meanwhile, I’ll keep archiving the present and wait for it to miraculously turn into the past.

Ken FreedmanFREE MUSIC ARCHIVE

When bands and artists perform live on the air, we ask them to license their performance under an alternative copyright license known as a creative commons license. The idea behind creative commons is “some rights reserved,” as opposed to “all rights reserved.” Most bands do sign the release, and then we can put these files available for the public on our Free Music Archive (www.freemusicarchive.org). The FMA now houses 100,000 songs, all available to the public and free for non-commercial use. We started the FMA with the aim of creating an online library for podcasters and royalty-free webcasts, but this library’s most popular use is among film and audio documentarians, who seek free or low-cost music for their creations.

Music that is performed live on the air is relatively easy to license and archive. It’s our other 400,000 records that exist on vinyl, cassette, LP and 45 that present the challenge. For all the insurance that we carry, the only radio asset that could never be replaced is our physical record library. That, and the stuff in the crawl space above the ladies room.

So we’ve begun planning out how we might raise the money to digitize the entire record and historic archive library. What we’ve learned is that the audio part is not the hardest part. The real time-consuming part is digitizing the record art, the liner notes and the tags. LPs present a real challenge, since the typical LP cover exceeds the size of typical flatbed scanners.

We’re working with the Internet Archive and New York’s ARChive of Contemporary Music for this project, and we’re at the very early stages of it. My staff is engaged in a lively debate over whether the project is better described as Herculean, or Sisyphean. As soon as we finish, I’ll let you know.

Tell us about your own radio history preservation efforts at[email protected].