For the past 45 years, the equipment design philosophy of Inovonics has been “Simplicity in design, consistent with performance objectives.”

For the past 45 years, the equipment design philosophy of Inovonics has been “Simplicity in design, consistent with performance objectives.”

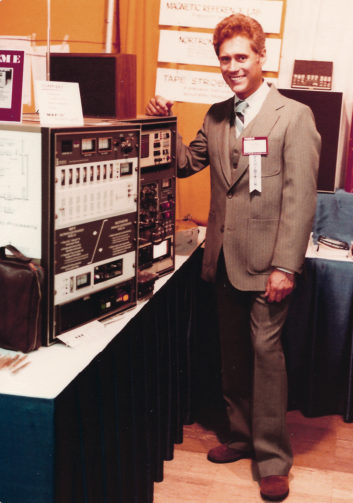

It’s a suitable mantra for a broadcast manufacturer whose corporate personality reflects that of its founder: quiet, dignified and widely respected. It’s a policy that has produced a lifetime of close personal relationships for Jim Wood with employees, fellow designers and manufacturers, radio engineers and station owners.

Wood, a recent recipient of NewBay’s Industry Innovator Award, spoke with RW about his earliest interests in electronics, his career and some milestones in the history of his company.

VIDAR AND GRT

Wood, 76, recalls that his interest in electronics began when he was about five years old.

“My dad had been a ham radio operator in the 1920s. He had a box with old equipment that I used to play with. That’s what fostered the initial interest. When I was around 10, I started building crystal sets, and got interested in pirate broadcasting and sound recording.”

He initially hadn’t considered electronics as a career, earning an undergraduate degree in theater arts with a minor in industrial arts from San Jose State University.

“I was informed by a professor in the Theater Arts Department that my portrayal of Willy Loman in Arthur Miller’s ‘Death of a Salesman’ was the most ‘unique’ one he’d ever seen in his life,” he recalls. “I took this as a hint that a career on the stage, movies or TV was probably not in the cards, so I followed my lifelong hobby-related interest in radio and electronics.”

His education in the business really began after graduation in 1964, when he went to work as a test technician for Vidar Corp. in Mountain View, Calif. It made instrumentation equipment, temperature gauges, strain gauges and similar equipment.

“The circuitry was analog, but they were beginning to transition to digital. The company was staffed by a lot of Stanford graduates. From them I learned how to make transistors do interesting things.”

After Vidar, Wood was a production engineering tech for General Recorded Tape, which in addition to producing tape product for about 30 record labels developed high-speed duplicators for 8-track tape and cassettes. Following efforts to diversify into unrelated industries, it went out of business in the late 1960s.

It was in 1972 that Wood partnered with Mark Drake to found Inovonics in Campbell, Calif. The two saw a market for replacement electronics for professional tape recorders, in particular those made by Ampex and Scully. The electronics for many of these machines used first-generation transistor circuits or, in the case of the Ampex 350 series, vacuum tubes. The original manufacturers had no interest in providing updated electronics.

Wood handled electronic design, Drake did the packaging. In what has turned out to be an ongoing practice, Inovonics talked to potential customers — in this case, recording engineers — to learn more about their needs and expectations. Wood said he found a great deal of room for improvement in recorder electronics, in both features and performance.

By the early 1970s, even basic opamp circuits could run circles around those early transistor and mature tube designs, and the smaller size of components meant that Inovonics could offer replacement electronics in a package the same size as the original, but with more features.

[Read more history: In Haiti Inovonics Lends a Hand]

Enhancements offered by Inovonics included the ability to remotely switch all monitor and equalization functions, the use of solid-state switching to eliminate contact issues and harmonic and phase distortion nulling circuits.

The original market for Inovonics’ tape recorder electronics was not broadcasters but recording studios. The premiere Model 355 was developed as a feature-packed stereo chassis. The marketing plan soon had to be changed.

“The studios turned out to be an unstable market in many ways,” he said. “I thought that radio might be a more solid market base, and it was.”

For radio customers, a mono chassis was needed, and the Model 360 was introduced. The sales pitch was difficult to argue with: Spend $690 for Inovonics 360 replacement electronics, install it in your Ampex 350, and come away with a machine having performance equal to or better than most modern recorders.

SUPER TAPES

Over several years, Inovonics focused on refining recorder electronics and adding to the product line. A new 380 series was an upgrade from an earlier 375. It included advanced features such as circuitry to reduce the effects of tape compression and phase distortion, expanded signal and bias headroom to accommodate high-coercivity tapes and extra bias and EQ settings to work with “super tapes.”

In 1989, Inovonics introduced its final product for magnetic recording, the 390 series film recorder electronics package. It was designed to replace obsolete sound electronics in motion picture recording and playback equipment.

By the late ’80s, digital audio was gaining a foothold, and it was clear that the days of analog tape recorders were numbered. Wood had built compressors and limiters for his garage studio, and began to explore the market for commercial audio processors.

“The market was dominated by the CBS Audimax/Volumax and Gates Sta Levels at the time. We had built the Model 200 and 201 for recording studios, and took one to KFWB Los Angeles. The engineers talked about their requirements, and we listened. The result was the Model 220, a mono audio processor for AM that could be paired with a second unit for FM stereo.”

A less-familiar Inovonics products was the Model 210 Frequency Selective Limiter. “It was originally developed while I was working at GRT, and patented there. However, we purchased the patent for $1 when GRT went under. The unit was repackaged, still mainly for tape duplicators, but with plug-in cards for different protection characteristics in anticipation of use for the unit in FM broadcasting.”

Eventually there were four audio processors in the product line. The new units sold well, and by 1980, Wood recalls, about half of Inovonics sales were audio processors, the other half replacement recorder electronics.

Mark Drake left the company years ago to pursue other interests but Wood has been its face and mainstay. Over ensuing years, Inovonics branched out into AM and FM modulation monitors, RDS encoders and rebroadcast receivers. As new products were released, others seemed to suggest themselves. When web streaming became more popular, an internet radio monitor was introduced.

PROUDLY AMERICAN

Wood is proud that Inovonics manufactures all its equipment in the United States. “It’s very important for us to support the local and U.S. economy.”

At one time, all assembly took place in the factory, but with advances in technology, some adjustments were necessary.

“When circuit boards had through-hole components, we could fabricate our own boards and then stuff them in-house. Surface-mount technology requires some very expensive equipment for assembly, so the board fabrication part of the process is now outsourced.”

Final assembly and quality control checks are completed at the Inovonics factory in Felton, Calif., where 14 people are employed.

In addition to the shift to surface-mount technology, another big change in equipment design and manufacturing is the dependence on software. Very little of the traditional circuit design takes place any more. Most of the magic of the latest generation of broadcast equipment lies in the use of digital signal processing (DSP) and other software.

“We saw this change coming, and wanted to keep all the development work in-house. We hired people with training in software engineering, and set out to build our first product.”

The Inovonics TVU was the first device that used CMOS logic and an EPROM. It displayed stereo audio level metering on the screen of a video monitor. When connected in-line with the monitor’s video signal, it inserted into the picture a boxed audio level bargraph that could be positioned anywhere on the screen.

HISTORY’S LESSONS

Wood’s role at Inovonics has changed over four-and-a-half decades.

“I used to design all the equipment, but my input in that end is about 10 percent now. I understand the concepts, stay focused on the big picture, and make sure the demand for new products is being met by the technology.” In addition, Wood writes the Inovonics tech manuals. “It’s something I enjoy, and I come away with a better understanding of our new products.”

Ben Barber joined the company as a test and R&D tech and engineer in 1988 and was named president/CEO in 2012. Wood today remains chairman of the board.

From the beginning, Inovonics sold into a global marketplace. In the early years, the biggest international consumers were in the United Kingdom and France. Wood adds that over the years, exports have ranged from 10 percent to 80 percent of Inovonics’ sales.

He noted differences in doing business abroad and in the U.S. “The cost of manufacture is usually less overseas, and we see some real innovation in products, particularly from the Czech Republic. They have great success selling to pirate broadcasters and smaller operations.”

Despite the price differential, Wood said Inovonics has a strong market position abroad, particularly with government broadcasters.

“Much of the equipment built by these smaller companies does not have the same quality of manufacture as gear from U.S. companies, and might not hold up well in 24/7 operations. Government broadcasters want the good stuff, and can be very demanding customers. They can have unrealistic demands, such as signal-to-noise ratios in excess of 100 dB.”

[Read: Inovonics Joins WorldDAB]

Inovonics is a company that likes to emphasize “the basics.” As expressed on its website, this means emphasizing service, ease of use, fair prices and “respect for our customer’s time, money and trust.” The company is also one of the few in broadcast with a section on its site devoted to its own history. For Wood, that is important.

“History can teach us some vital lessons, and it’s good to occasionally reflect on some of our milestones. You can’t dwell on it too much though, because you need to keep up with the times. If we hadn’t gotten ahead of the curve when digital was coming and hired new people, Inovonics would be part of history now.”

Part of being ready for the future involves taking risks. Not all of them pay off.

“We got involved with Motorola AM stereo and CBS Lab’s FMX, which just weren’t going to fly, so it’s just as important to know when to cut your losses and move on.” On the brighter side, Inovonics was an early promoter of RDS, an investment that has certainly paid off.

A testament to the quality of Inovonics equipment lies in the fact that so many of the original recorder electronics remain in service, some 45 years after they were built. “There are still quite a few channels in use for archiving and to play ‘legacy’ tapes from the archives. There are also many channels of film record/play and play-only electronics in use, as Hollywood has so much material still on full-coat 35 mm film stock.”

Looking ahead, the company will introduce a new RDS/RBDS encoder at the NAB Show this year, Model 732, which Wood says will make setup and programming much easier and include a true web interface.

Reflecting on his career, Wood said the best choices aren’t always about making a lot of money.

“There are easier and more lucrative ways to make a living. But something very special about radio appeals to so many of us. We’re here because we love it and want to be a part of it.”