At a recent AES convention, Paul McLane, the U.S. editor in chief of Radio World, chaired a broadcast session on facility planning in which a number of questions and topics related to planning and building a broadcast facility arose.

This article documents some of these topics and offers insights on what to do and what to avoid when planning a technical facility.

In projects of every size, cost is always a serious consideration. Remarkably, the initial projected cost is almost never on target, and the cost of almost every project tends to sneak upward.

We have seen facility owners and planners make a number of mistakes which, if eliminated, can substantially reduce this disturbing trend.

One control room supports two talk studios at Air America in New York What are the biggest mistakes facility owners make and best practices you can suggest?

There is a real and valuable need for facility owners to define clearly the needs of the facility, in terms of operations and architecture, as early in the project as possible.

Documenting such issues is the best step one can take to get everyone on the design team on the same page. Setting the program for a facility as early as possible allows a realistic budget to be defined and controlled.

In our experience, the more effort that is put into a space-by-space programming document, the more likely that the design and construction team will stay focused on the needs of the facilities and identify costly design or site-related issues early on.

Often, changes to the design late in the process force costs upward in large and unavoidable steps. Remember, it is almost always easier to make changes on paper early than to make them in wood, steel and drywall once construction has started.

To start the facility planning process, we urge clients to write a programming document for the facility with each space described in terms of its projected functions. For each space, define at least the following items:

- • Number of users working in the space (typical and maximum)

- • Critical adjacencies (other studios, closets, offices, windows, etc.)

- • Amount and type of equipment expected to be installed. Amount of power required and heat generated by this equipment should also be listed.

- • Any special isolation conditions that require attention — anything near a demising wall, critical neighbors above or below or even adjacent spaces within your facility (a demising wall is a boundary that separates one tenant’s space from that of the other, and from the common corridor)

- • Special needs (lighting control, look, feel, size, tech tie-ins, etc.)

As with a business plan, we expect this document to start off full of holes, blanks and inaccuracies. It is just a starting place. We want the programming document to change during the schematic process, which will help to define priorities and limitations of each layout and changes under consideration.

During the schematic and programming phase, we encourage our clients to dream about both the short-term needs and longer-term hopes for the facility. We then can see what items are required to operate immediately, and plan, at least in terms of infrastructure, for future uses.

Small additions to the cost of conduit and accommodation for cabling can save huge amounts of money and inconvenience later.

Once a schematic layout is defined in conjunction with the programming document, a realistic “actual” cost can be estimated.

While it is common to start with a target budget, we urge our clients to define the facility they want, develop a programming document and initial layout, then develop a cost estimate. We then can work as a team to select how they scale it back to meet the budget if required.

One example of how this process works: A New York facility wanted to add two radio studios, each with its own control room, each large enough to host a six-person discussion show.

We encouraged the facility owners to create a full programming document. Using this as a basis, we studied the layout of the space available and found we could not fit the desired spaces into the space available.

Working with the facility management and engineers, we suggested a layout that provided one over-sized control room that supports two larger “talk studios.” This configuration met the facility’s operational goals; it allowed for future expansion by including lighting grids; and it was built on budget.

How are the demands of multi-platform broadcasters changing design of facilities? Are radio stations changing the way they design facilities to include real video content functionality and “new media”?

As so many traditional radio studios now host video shoots, we are seeing a trend to add infrastructure to new studios that will support the future addition of production lighting and camera locations, even when there is no immediate plan to add this equipment.

While adding cameras presents only a relatively small cabling issue, lighting grids can require substantial electrical and cabling. Several new facilities have added lighting grids and dimmer support cabling systems to new studios but have not purchased full production dimming systems.

Lighting systems that allow flexible lighting positions and creative dimming in conjunction with some visually acceptable wall treatments seem to the keys to making “casual-in-studio” video look good.

In most cases, the cost of a grid is relatively small and has only minor impact on the cost of the structure of an isolation ceiling. However the cost of a production dimmer system that is acceptable to a video team is often more than a new facility may want to spend. A studio with a grid and cabling and power support in place can allow a rental lighting system to be added to in a few hours, without disrupting the work flow of the facility and adjacent spaces.

What HVAC parameters must a planner consider?

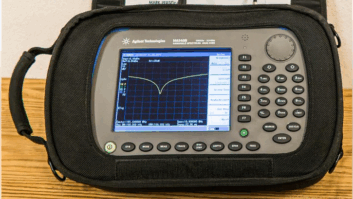

(click thumbnail)

Layout for a studio at Air America It is not uncommon for the HVAC and electrical part of a broadcast facility to consume more than 35 percent of a project budget. Adding to the cost is the use of larger ductwork, often with acoustical duct-liners, in-line duct silencers, multiple control zones, exterior duct wraps and low-noise grills.

The amount of cooling required is a result of well-insulated rooms and equipment. Last, the use of ducted returns (used to control sound rather than simple plenums) adds considerably to the cost of a typical studio’s HVAC system when compared to a typical office environment.

A common, often costly error is waiting until late in the design process to involve your HVAC engineer. We urge clients to engage their mechanical engineer as early as possible and demand the delivery of a “one-line” drawing that represents the paths of desired duct runs, as early into the schematic design as possible.

With this drawing in hand, all parties can consider and review the duct runs during the schematic design phase, reducing the likelihood that expensive changes required by the site conditions or other design considerations will be required later.

Obviously every situation is different; however, careful management of the design process can substantially reduce many of the most costly design and construction problems that many studio facilities run into.

The author is managing partner of SIA Acoustics and founder of SIA Software Company.

Sam Berkow’s acoustical design projects include work for Jazz at Lincoln Center, the Grand Ole Opry, Air America Radio, “This American Life,” WBGH in Boston and others.