America has long had a strange ambivalence towards quality. In electronics, the elements of quality’s triple crown — performance, perks and price — are in constant contention. We always want more, for less.

Radio was a revolution in the 1920s and ’30s, uniting a country through current events, issues, entertainment — even through time, because most clocks in America were set to network time then. A radio was an investment. A home’s receiver occupied a hallowed place in the living room or wherever the family centered its lives. Economies limited the secondary uses of radio, so manufacturers developed a unit so inexpensive that “second sets” became affordable.

Value engineers — the guys who identify a goal and then ascertain how to reach it at the lowest possible price — set out to design a radio circuit suitable for mass production, one that could fill this need. It was a sort of Model T for the ether. It filled a sales gap for its makers while filling bedrooms, garages, workshops and offices with radio’s benefits.

In the ’30s the number of stations increased; most of the new ones were in rural settings, closer to their listeners, hence moderate sensitivity in the unit’s design was acceptable. Also, utility power now was available to a vast majority of Americans; line voltage was standardized such that designers could anticipate 100 to 130 volts.

The result of this quest was the “All-American Five.” This five-tube circuit was atypical; its design is not credited to a specific person or firm, to my knowledge.

If a progenitor could be identified, that most likely would be the tube manufacturers — probably more specifically RCA. The introduction of improved, innovative tubes, mainly by RCA, gave designers the ability and impetus to explore new approaches.

This novel circuit was stripped down for action. The engineers eliminated the power transformer by using a DC voltage at about 150 volts, achieved by rectifying the line voltage directly and after filtering had a low but workable B+. A filament transformer was eliminated by stringing a series of filaments; each had the same current consumption with a total voltage drop that equaled a nominal 120 volts. Typically also absent were wide audio response or a tone control.

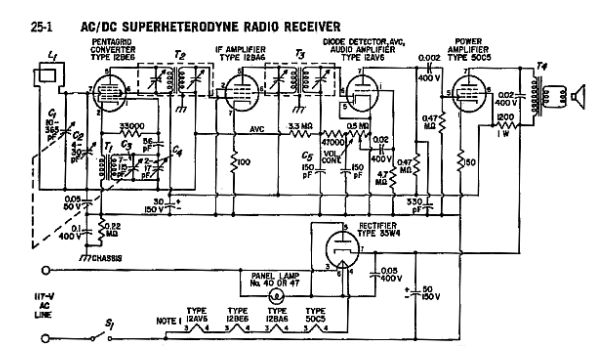

Over the years, although the tube quintets might have changed numbers (see the schematic below for a typical group) or become miniaturized, the functional stages mostly remained the same: a pentagrid oscillator/converter, an intermediate frequency (IF) amp, a multipurpose tube (detection, AGC and first-stage audio amplification), an audio power output stage to drive the speaker and a B+ DC rectifier. The design just barely qualifies as a super-heterodyne receiver.

My best surmise is that the RCA AA5 with a wood cabinet shown in the accompanying photo was made during the 1940s in Camden, N.J., probably in the famous Building 17, part of the Victor Record Company complex (RCA Victor, the Victrola brand). The assembly line used gravity to great advantage. Starting on the top floor, radio production for that day would begin with the bare chassis; as parts were added, these batches of subassemblies would be rolled down wide ramps to floors below for continued work until arriving at the cabinet shop and shipping at ground level.)

Americans must have been delighted with the products they were able to buy at an affordable price, judging by the quantity of AA5-type radios sold.

As we’ve mentioned, it’s not how these boxes worked but what they did that’s most important. The ubiquitous AA5 design took radio to new locations where it could be heard by more ears and for more hours. These radios gave stations an increased audience and allowed the industry to grow.

Millions of AA5s were made by a myriad of manufacturers; thousands are still in use even now. The Web has lots of information if you’d like to know more about the history of the AA5. See here and here. Also check out Wikipedia’s All-American Five listing.

Next time we’ll talk about my even more minimal radio — the AA4 perhaps? — and how it changed my life.

The next “big thing” that turned radio into a new mobile, personal and intimate accessory was the transistor portable. We’ll talk about that phenomenon in this story.