If your station uses an off-site traffic reporting service or if your traffic reporter doesn’t have line-of-sight with your air talent, I’m sure you’ve heard the air person introduce the reporter only to be met with dead air. Not only is this embarrassing but listeners may feel the lack of a traffic report is the talent’s fault.

Let’s face it: Such problems simply sound unprofessional. KQED(FM) San Francisco Chief Engineer Larry Wood, CPBE, worked with the Total Traffic & Weather people and iHeartMedia engineers to develop a solution. Even though the reporters are by and large reliable, he says, this fix ensures that every report airs.

Fig. 1: An LED sign lets the operator know the traffic reporter is ready.

Fig. 2: The sign is mounted so that it is visible to the board operator. Being associated with KQED(TV) has its advantages. Image Video signs, common in TV stations, provide a matrix of multi-colored LEDs that can spell out warnings or notifications to air staff. There are lower-cost versions that may be more suitable in radio settings; see www.imagevideo.com or ask your favorite broadcast equipment dealer.

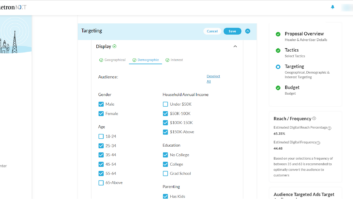

So Larry took advantage of the contact closure provided in the Comrex BRIC-Link boxes that connect the traffic center to KQED. Your audio codec probably has contact closure capability too. As soon as a Total Traffic & Weather Network reporter selects KQED as a destination for a report, a closure is sent to KQED via the BRIC-Link. The phrase “Traffic Ready” phrase appears on the Image Video sign in green LEDs, as seen in Fig. 1.

This lets the local announcer know that the traffic or weather reporter is ready to send a live report when cued. The occasional miscommunications or delays are avoided.

Larry has taken advantage of the Image Video LED sign to provide additional text messages for the air staff. These include EAS alert, audio fail and transmitter off-air alarms, loss of HD audio, hotline ringing, and various NPR, T-1 and STL feed alarms. As shown in Fig. 2, the sign is visible to the board operator.

This next tip comes from Greg Muir of Wolfram Engineering and should be filed under the heading “There’s always time to learn something new.”

The local power utility told Greg it needed to cut power to one of his transmitter sites for the day in order to reroute the HV primary power feed from another pole and install a new cross arm on the existing one. The site has backup generator power so he wasn’t worried interruption to the six transmitters housed inside.

The utility cut the power, the generator started and all was well.

The utility crewmembers disconnected the feed to the building on the pole and then measured the voltage on the phases at the outputs of the transformers. They found the voltages all over the place, looking suspicious. Working on the premise that they may have a bad pole pig, they ordered up a new one and installed it in place of one of the three existing units.

But now things looked really bad.

Greg told the crew that everything had been hunky-dory before they disconnected power, so he was skeptical about what they were seeing. When he returned to the site later in the afternoon, the crew had changed the span and two were still up in the bucket truck; the power drop to the building was still not connected. And now there were four or five more people present, some from the utility’s engineering department. All were scratching their heads about seeing such squirrely voltages out of the transformers.

Greg went inside the building for about 20 minutes. When he came back out, one of the crew gave him “thumbs up.” Greg walked over and asked what they’d found; they said they had two bad digital voltmeters. (Are you starting to suspect something?)

Greg asked more questions and found that the bad ones were from a single manufacturer and were of Chinese origin; the third, which was working, was a nice Fluke meter.

Greg proceeded to educate the crew about effects of stray RF on digital voltmeters. There were silence and puzzled looks, followed by a lot of questions. Greg said that since the transformers were connected to the primary high-voltage side but not connected to the building (which would have presented a much lower impedance load and probably would have swamped most of the RF on the wires), what they probably had up there was a fantastic three-phase “antenna” coming up to the pole loaded with lots of near-field RF, which promptly accompanied the measured AC voltages into the Chinese voltmeters — and thereby affecting their readings.

It was a little hard for the crew to accept his theory, especially after they’d spent five hours fighting the “problem;” the utility engineers also were a little miffed. So Greg took one of the Chinese meters and asked a crewman to hold it in his hand as he stretched the test leads out in a dipole fashion. The meter began to read voltage, which convinced them.

Greg asked if they had any old Simpson 260s lying around. They did, in a box in their warehouse. Greg suggested they throw some in their trucks just in case they encounter work at another broadcast site.

The cheaper DVMs are nice to have and may work in a pinch, but Greg’s experience suggests you not put all your faith in them, especially in an RF environment. Those old Simpson 260s may be from another era but if you don’t have a Fluke, you can usually trust their readings.

Contribute to Workbench. You’ll help your fellow engineers and qualify for SBE recertification credit. Send Workbench tips to [email protected]. Fax to (603) 472-4944.

Author John Bisset has spent 46 years in the broadcasting industry and is still learning. He handles West Coast sales for the Telos Alliance. He is SBE certified and a past recipient of the SBE’s Educator of the Year Award.