Jelli Co-founder and CEO Mike DoughertySAN MATEO, CALIF. — If you listen to advertisers or their agency reps, programmatic ad buying is a big trend for categories such as digital display, events, online video and mobile. In those categories, “programmatic” has surged over the last three to five years.

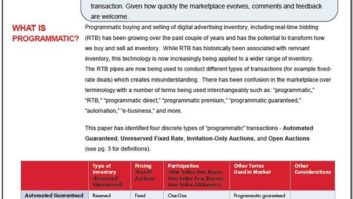

Think of programmatic as an electronic methodology for accessing inventory and then pricing, selling and buying it.

Automatic ad buying and selling has made big inroads in the digital display market that serves laptops, mobile phones, tablets and desktops. There, programmatic ad spending was expected to grow 137 percent to more than $10 billion in 2014, according to eMarketer, which would mean automated ads would account for nearly half of the U.S. digital display market. That dollar amount was expected to double by 2016.

Advertisers and their agencies have said they would like to enable programmatic trading across their entire media buys, representing as much as 50 percent of all media spending. Few of these dollars have come to radio yet, but supporters say automated buying and selling can return money to radio that has migrated to mobile advertising, which advertisers find easier to transact. U.S. commercial radio revenue in 2013 was $17.6 billion, according to the Radio Advertising Bureau.

One of the promoters of programmatic ad spending is San Mateo, Calif.-based Jelli, founded in 2008. It has raised some $16 million in venture funding from investors including Relay Ventures, Intel Capital and First Round Capital as well as several angel investors.

The company’s original focus was crowd-sourced radio; however for the past couple of years, Jelli has shifted its resources to programmatic and its RadioSpot platform.

Jelli co-founder/CEO Mike Dougherty worked in the ’90s as a investment banker before becoming senior vice president of business development and strategy for digital music and video platform Loudeye in 2000, later acquired by Nokia. He then held a similar position at the telephone-based application company Tellme, which was acquired by Microsoft in 2007.

Dougherty spoke with Radio World News Editor/Washington Bureau Chief Leslie Stimson about Jelli and the programmatic trend.

RW: What is programmatic buying? I keep hearing that television is doing it, so radio should also.

Dougherty: Programmatic is a methodology of buying and selling advertising. You automate more steps in the process of selling and buying the ad. …

One of the core technologies that was put in place about 15–20 years ago in digital was an ad server, DoubleClick, which was acquired by Google. It allows ads to be tracked, delivered, reported on and even targeted in a way that’s more precise. … The second part of programmatic is the idea of targeting. So you’re now thinking about new, sophisticated ways to use data to target audiences.

An example may be that Nielsen provides new service to the market that gives you better insight on household income or whether you have a propensity to buy a Lexus or drink Budweiser. It’s third-party data — information that’s beyond the traditional demographic [and] about your propensity to do something.

You can use [programmatic] data to get a better insight as to which properties you should buy, because those are the properties that skew more closely to what you want. In the case of a website — a digital sale — you can target an individual with a cookie, so you don’t have to even think about the website; you can just go after the person using that data.

In the case of a radio or TV station, obviously there’s a blended group of people that are listening. So you’re going to have people who aren’t just interested in Lexuses or people who are male and female. But the data allows you to reduce the waste so you find the media properties that have the closest alignment to the list of things you’re looking for from the audience. The third-party data sources get applied in almost a big data overlay across these stations, and you can essentially pick them better. You don’t have to just use format as one tool of targeting. …

There’s also a new category called first-party data, where brands that advertise have their own data about the audience. This is where it gets kind of cool and fascinating — where Wal-Mart knows, based on things like weather, whether people want to buy raspberries. They use that big data to say: “I want to trigger campaigns now on TV, radio and digital using my own data that’s proprietary, about my consumer base.”

Now you can target what you buy in a way that is more sophisticated than the old RFP or insertion order sale.

The last part, prevalent in digital display advertising, is starting to come more to online video but not in radio; and that’s real-time bidding. Sometimes people associate programmatic with a real-time auction, almost like a stock market where you’re trying to out-bid somebody to buy the spot.

RW: You’re bidding to get it at a certain price?

Dougherty: Correct. Once you’ve gone through your analysis — I really want these stations and I want these dayparts because of my big data analysis I’ve done and these are the right stations for me to target a Lexus buyer. Then I can put in a price to outbid everybody else to buy that inventory.

Real-time bidding, which is essentially an auction format for advertising, is happening in a big way in digital display advertising in something like half the market. But it’s a very small percent of the market for TV. It’s a controversial concept as well because the traditional broadcasters are concerned that real-time bidding could lead to price erosion where the bidding dynamic actually drives down the value. Sometimes people call it RTB; the nickname is Race to the Bottom.

RW: A fire sale.

Dougherty: It’s like an eBay auction where people are using that to their advantage, on the buy side, as well as the sell side.

With Jelli’s Radio DashPad analytics, buyers see their ad running in real time on all the stations on which they bought time.RW: Are they bidding online?

Dougherty: There’s a tool used by the buyer and the seller to participate in those exchanges. The ad inventory is published into the exchange … a pool of available inventory. That publishing step typically comes with price controls, where if you’re selling the inventory you own, you would say, okay, I’m interested in someone buying this. They can bid on it if they want. But I don’t want to sell it for beneath a minimum price. So, you can’t bid lower than X. But you can bid it up, if you want. [You] put that into the exchange.

Buyers are using these big data techniques to say I really want to buy these things right now. What’s available? What’s the price? If there’s not a lot of people buying it I can just get it for the price I want, but I may have to bid it up to get what I want. That’s the exchange. Many big exchanges exist for digital advertising, for something like $10 billion in the U.S. this year.

RW: What’s an example?

Dougherty: Google’s DoubleClick has one. On the digital side there’s also companies that power those exchanges. One example is AppNexus, rumored to be big enough to go public. Another is Rubicon Project, which is public. There’s also a company called PubMatic. They’re powering selling on the digital display side. AOL bought Adap.tv — an automated exchange for video advertising.

It’s a really complex world because there are so many people doing it, but it’s not radio. Jelli has some services that are enabling radio groups and radio networks to sell their inventory in the same way these digital display companies are selling and buying their inventory. We have a platform that’s similar to some of those companies.

RW: That’s your SpotPlan?

Dougherty: RadioSpot is our ad server. SpotPlan is the tool to use to identify what you want to buy and try to figure out what the best plan for you is to buy, using real-time inventory and price. It takes price and inventory and places those in the cloud. It says here’s what’s available. Here’s the price. Do you want to buy it? And if you say yes, then it will essentially buy that inventory. You’ll upload your radio spot into the cloud and that spot will be automatically cached or delivered down to all the different RadioSpot servers out there and gets scheduled to run on the air.

When your ad … airs, SpotPlan will create a real-time log that’s published back to a Web tool called RadioDash, which is your dashboard. You’ll see your ad running in real-time on all the stations that you bought. You can have dashboard analytics to show you, here’s your campaign, you’re about 46 percent done running the campaign. It’s going for another week or two. Here are the spots that have run so far. You can listen to them. …

It brings the concept of analytics to radio ads so that a buyer can now do more with the information. “I’m running ads in Boston. Are my sales going up this week in Boston?” It also puts radio on the same page or on par with digital analytics so that we don’t look out of place — so that we have the same ability to provide real-time reporting, so that the client doesn’t feel like radio is harder to work with or more delayed or feels more “legacy.”

RW: And the real-time log is a way of proving that the ad really ran.

Dougherty: Yes, if you think about it from a metaphor perspective, it replaces the affidavit. In the traditional world the station would create an affidavit using your system to say “I ran the ad,” and you would send that affidavit either to your ad network or to the advertiser to prove that the ads ran.

What [Jelli’s] log does is it gives access to the advertiser directly so that they can see the time-stamp and the ad running in real-time. They can look at their campaign themselves and see all the different reports.

RW: Having been on the air, I can say sometimes we weren’t as focused on the ads as we should have been.

Dougherty: Running a radio station these days is harder every day. You’ve got a smaller staff than you did 10 years ago … The irony is the complexity is increasing … That complexity is hard because radio has not been able to keep pace. … When the agency puts in a request to the radio station for more information, they don’t get anything back quickly; it’s hard for [radio] to react to their clients’ needs.

RW: So if I’m understanding what you’re saying about programmatic, it’s more automated than the current system, more targeted and it’s becoming more prevalent in other media, and radio needs to catch up?

Dougherty: That’s fair. The more prevalent part is important because I think there’s a lot of people in radio who are thinking, this is a buzzword or I never heard about it so it can’t be big. … And I think it’s because local advertising hasn’t gone as much to programmatic as national advertising has. So if your world consists primarily with dealing with local advertisers on a local station, your clients aren’t telling you about programmatic; but if you deal with national advertising, you’ve already heard this term. This is a big deal in the national advertising world.

RW: Is this for on-air, websites, streams, analog, HD Radio — every distribution platform a station has?

Dougherty: It is; however right now it’s provided by different participants for each of those channels. So Jelli provides [programmatic] for the on-air broadcasts. There are a few companies that provide it for streaming audio that aren’t Jelli, and they don’t do broadcast. Examples are Triton Digital, Abacast [acquired by WideOrbit in 2014] and AdsWizz. … For a website, you’re probably going to work with DoubleClick or somebody who you’re working with on display advertising. Right now, programmatic vendors don’t have a unified platform. … I think that will happen at some point.

RW: Marketron and Jelli say they are trying to make programmatic buying easier.

Dougherty: On the broadcast side, Marketron has a large footprint of providing ad traffic software for thousands of radio stations. They have partnered with us to allow that core software used at stations to unlock new functionalities so that you can use your Marketron software called Mediascape to sell programmatically. You don’t have to learn a new platform and it allows you to put some of that inventory in front of buyers who are buying programmatically. So it allows you to sell more inventory.

RW: How many stations is Jelli doing this for?

Dougherty: We have more than 400 stations on our platform. We also have partners who are using our platform as the infrastructure to do this for their clients. [Radio clients include Townsquare Media, Entercom, Emmis-owned WQHT(FM) in New York, and several Beasley Broadcast Group stations.]

RW: So the advertisers and their agencies are pushing this?

Dougherty: Correct. That’s the part where you say it’s coming to the table because of a bigger trend. Programmatic is surging in these other media types and everyone thinks radio is very attractive. So they’re asking radio to hook up to platforms that will enable the advertiser to buy radio in the same way they buy these other media types because they want to add radio to the media mix.

If you think about it, if I’m spending a lot of money on Facebook and a display ad campaign, that’s pretty effective, but boy, wouldn’t it be nice to reach someone in the car because I’m an advertiser who perhaps is a retailer, and they can drive to my store. The core value of radio remains very powerful, but if they’re buying all their campaigns with these programmatic platforms, it’s simply not an option for them to add radio. What they’re excited about is the fact that radio’s coming online with these programmatic platforms like Jelli’s RadioSpot; now they can start adding radio into their buying mix.

Our goal here is to have advertisers who like buying radio to have more tools at their disposal. And advertisers who have not bought radio to look at us again or look at us for the first time as a medium to buy; and folks who have moved away from radio, to bring them back.

RW: Over the summer you shut down your crowd-sourced radio product where listeners rocket up or down the songs. Did that just run its course?

Dougherty: That’s right. It never really took hold the same way we saw with programmatic platform. Probably at our peak we were at 30 to 40 stations. Two years ago we got some feedback saying, “Your platform is pretty awesome and I love getting feedback from the audience, but could you use your platform for serving radio ads?” That was really the original pivot, which was we serve music files up every couple seconds all day with our platform; we can certainly handle a radio ad. That’s where it started to evolve where we started to work more with advertising agencies and radio groups around making Jelli an alternative to an ad server for a radio spot. …

At some point we had to make a decision because of resources. … Programmatic grew so much it was tough for us to continue to divert our attention between two different things, and so that was part of the reason we said that was a great run we had with the social radio platform but we want to put all of our effort behind programmatic advertising and that’s why we made that move.

RW: How many employees do you have?

Dougherty: We have about 25, mostly technology people. We have a team based in San Mateo—a city located in the Silicon Valley. We have employees from Google, Yahoo and Amazon [with] pretty deep technology backgrounds. They’re the ones building the platform.

RW: People with computer software coding skills?

Dougherty: Correct. We’ve also hired some people from the ad tech programmatic space. One of our product people we hired from Adapt.tv is trying to build the ability from the spaces that are already doing programmatic at-scale to radio. Programmatic is radio’s future, and Jelli is helping to change the trajectory of broadcast radio.

Check out the Feb. 1 issue of Radio World for more information on the programmatic trend.