The school of design called Art Deco reached its peak of development in the United States in the mid-1930s. The style is revered today in its surviving implementations — notably, in period buildings like those found in Miami’s South Beach; in the streamlined designs of automobiles, trains and ships; and in a variety of consumer devices from the period.

Art Deco reflected everything that was modern, and so it was only natural to see it applied to the new technology of radio. Thousands of Art Deco radio receivers were marketed to the public, and the more attractive surviving specimens bring top dollar at art auctions today.

This was also true on the broadcasting side, where beautiful Art Deco studio and transmitter buildings were created.

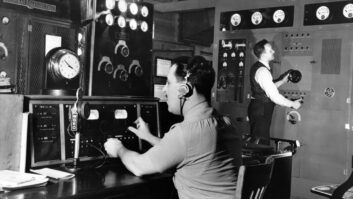

In this image, we see it applied to a stylish transmitter created by RCA. This 10 kW unit was installed in 1937 by CBS at its shortwave station W2XE in Wayne, N.J. With its streamlined styling and sweeping lines, this might be the most beautiful transmitter design I’ve ever seen.

W2XE was begun in the mid-1920s by Alfred H. Grebe, an early manufacturer of radio receivers. It rebroadcast the programs of his AM station, WAHG in New York City. In 1926, he formed the Atlantic Broadcasting Company and changed the AM call sign to WABC.

William S. Paley bought the AM and shortwave stations in 1928, and so WABC became the flagship station for his network, the Columbia Broadcast System. (To avoid confusion, the call sign was changed to WCBS in 1947, when the NBC Blue Network was sold and became the ABC network. The ABC station WJZ then took on the WABC call sign.)

For a number of years, W2XE was simply a relay station for the programs of WABC and the Columbia Network, the same as its other shortwave station, W3XAU in Philadelphia. But in 1937, CBS decided to get serious about international broadcasting and formed a Shortwave Bureau.

A pair of Vee (half Rhombic) antennas was aimed at Europe and South America. The rotary switch seen above the transmitter allowed its connection to either antenna. With more power and a high-gain antenna, W2XE then boasted an effective radiated power of 40,000 W. That was plenty of power to be heard around the world on the quiet shortwave bands of the time.

The new transmitter plant was dedicated May 12, 1937, by Elizabeth Ann Tucker, who was the new head of the Shortwave Bureau. She had worked for CBS Engineering since 1931 in a non-technical capacity. She soon developed a new program schedule that combined domestic CBS programs with special programs in English and Spanish for international audiences.

A QSL card from W2XE in 1939 shows operations on 6120, 6170, 9650, 11830, 15270, 17830 and 21570 kHz. The same transmitter was apparently used for all frequencies, and the station changed channels during the day as propagation conditions changed. Thirty-minute silent periods between frequency changes gave the engineers time to re-tune the transmitter.

In the 1930s, the FCC still considered shortwave to be “experimental,” as indicated by the letter “X” in the call sign. This meant that shortwave stations could not broadcast advertising, and this — along with the congressional prohibition against any direct shortwave broadcasting by the U.S. government — discouraged most shortwave investment in this country.

Meanwhile, Germany had a powerful presence on shortwave, spreading Nazi propaganda around the world. And so, to counter this, in 1939 the FCC eliminated the experimental designation, which meant that standard broadcast call signs were assigned. W2XE became WCBX and began a dubiously successful attempt at international commercial broadcasting. Meanwhile, NBC and General Electric were also attempting to commercialize shortwave radio with their own stations aimed at Europe and Latin America.

This short period of commercial shortwave radio came to an abrupt end in 1941 with the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Within a few weeks, all commercial shortwave stations in the United States would be taken over by the new Office of War Information for government transmission of war news and propaganda to the European and Pacific theaters.

To get around the legal restriction on government broadcasting, CBS and the other station owners continued to operate the transmission plants, but all programming came from OWI studios in New York and San Francisco, with all operating costs reimbursed by the government. CBS moved its shortwave plant to Brentwood, Long Island, in 1940, and in 1943 added two more government-financed transmitters, which were heard as WOOC and WOOW. They also opened a new West Coast shortwave complex at Delano, Calif., in 1944.

After the war, Congress finally did an about-face on the issue of government shortwave broadcasting, with the result that most U.S. shortwave stations were purchased outright by the government and became the beginnings of the Voice of America.

Even if World War II had not interrupted things, it’s unlikely that CBS or the other commercial broadcasters would have ever made any money with their shortwave operations. After the war, the shortwave bands found success only as an outlet for government propaganda and religious broadcasting. But for two short years, 1939 to 1941, the world enjoyed a brief taste of American-style commercial broadcasting on the international shortwave bands.

For other articles on early shortwave broadcasting, see these previous Radio World articles; find them with the given keywords at radioworld.com: “W6XBE at the Golden Gate Exposition, 1939,” keyword W6XBE; “WCAU Used Shortwave in Philadelphia” and “A Sequel to the Philadelphia Story,” both with keyword WCAU.

John Schneider is a lifelong radio history researcher. Write the author at [email protected].