Experts in alerting are keeping an eye on a project in Florida, where emergency management officials are harnessing the power of artificial intelligence in an effort to better protect residents from the threat of hurricanes and other natural disasters.

The statewide project involves technology from Futuri, a company familiar to radio broadcasters for its AI-based services.

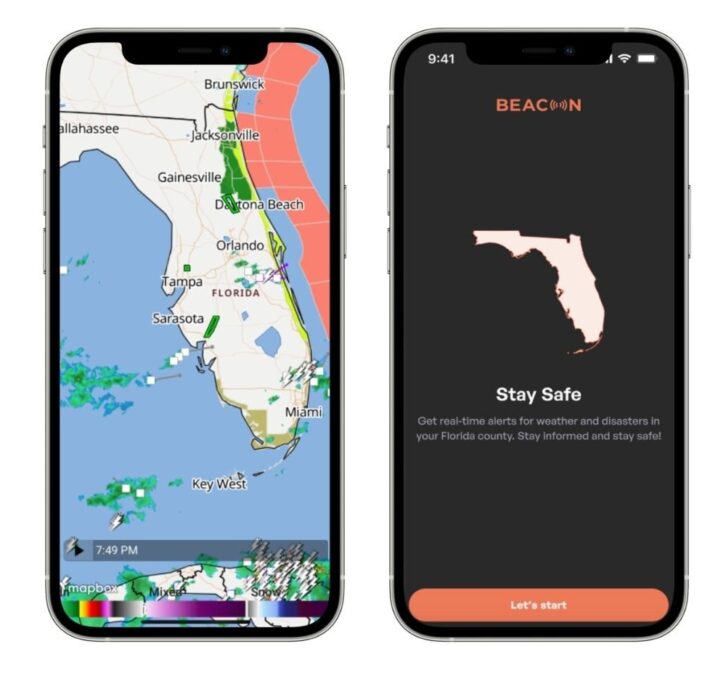

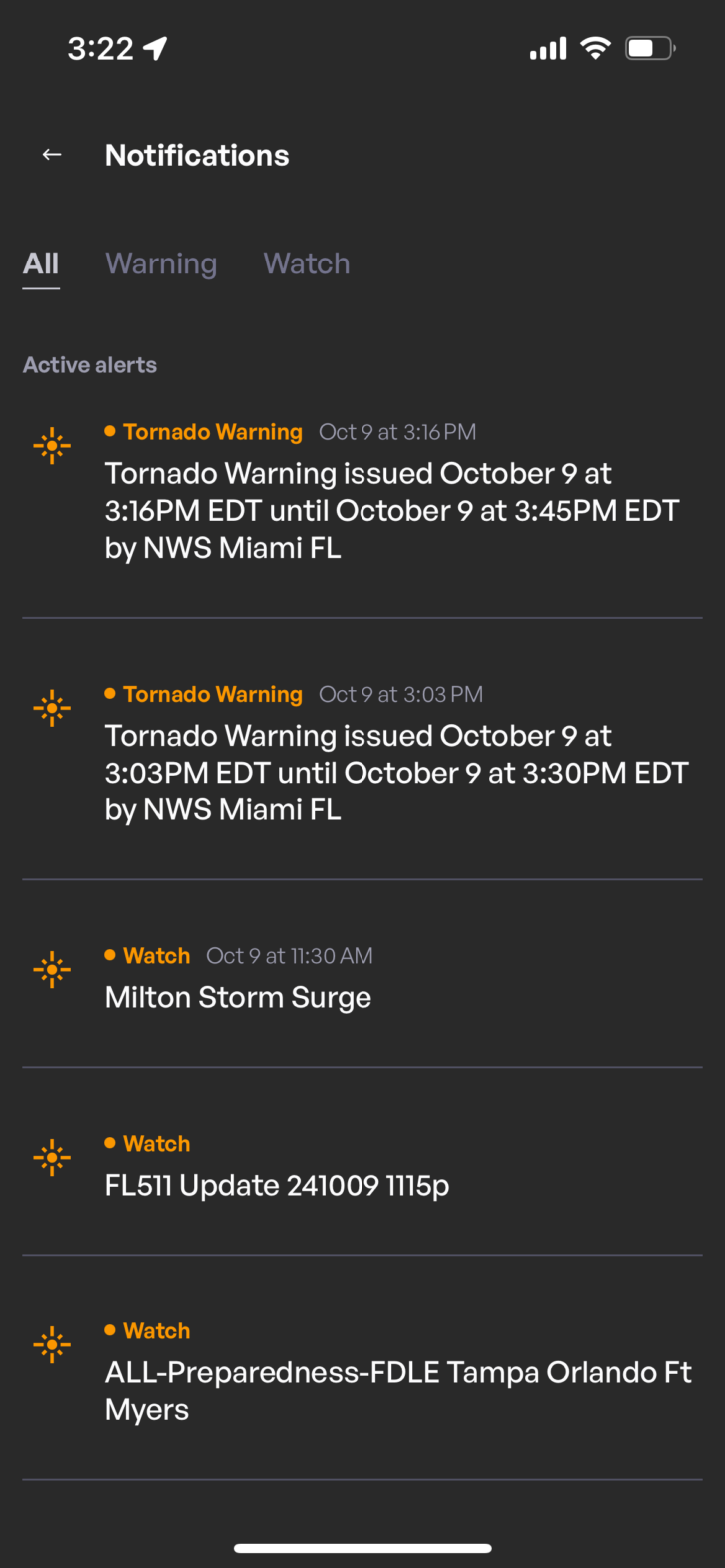

In December, Florida’s Division of Emergency Management, the University of Florida and Futuri announced the launch of the Broadcast Emergency Alerts and Communications Operations Network, or BEACON. They describe it as the first AI-driven emergency broadcast system to deliver disaster communications.

They say the platform combines the benefits of AI with the resiliency of broadcast technology to allow emergency managers and first responders to communicate with communities.

“While existing systems provide basic early warnings, BEACON revolutionizes emergency communication by delivering comprehensive, multi-lingual alerts throughout the entire lifecycle of an emergency — from initial warning through recovery,” according to the project’s website.

Former FEMA Administrator Craig Fugate is an executive consultant to BEACON and said it could be a model for a national system. Futuri, after testing its reliability in Florida markets this year, expects to offer the emergency system to other states.

The system automatically captures, prioritizes and translates public safety information from authorized sources, localizing the content based on geography and using AI to voice radio broadcast updates and advisories. It can also translate them into multiple languages, something the FCC has been hoping to do for EAS messaging.

BEACON has rolled out on 12 radio stations owned by the State University System of Florida, but the system also can be used by any commercial station in the state. It integrates into newsrooms and studios through a secure dashboard, allowing broadcasters to access real-time content.

It also is integrated with the Integrated Public Alerts and Warning System, so alerts in IPAWS messaging are captured in BEACON without a manual process, its developers said.

Information about the initiative can be found here.

Valuable follow-up

EAS experts contacted by Radio World for their reactions say this new communication system can be a compliment to EAS. They say state-based alerting systems can help “fill in the gaps as long as they are not splintering emergency alerting in the country.”

As one put it, “The more tools in the toolbox, the better, as long as the message is accurate and timely.”

Another observer said the system in Florida will likely serve as an “aggregator” to feed emergency information to broadcasters and across social media.

“They are welcome for development, but they should not take away from traditional alerting methods.”

Adrienne Abbott, chair of the Nevada State Emergency Communications Committee, told Radio World that with most radio stations and many TV stations operating on automation, an AI platform like Futuri’s would allow those stations the ability to serve their communities by providing follow-up information after an EAS activation even though their station doesn’t have the resources of an on-air staff or a news department.

“EAS is the headline for an emergency or disaster. That’s what it was designed to be, but what’s been missing for generations is the follow-up information,” she said.

“Of course, any AI system will have to find some way to assure the public that information presented is coming from an authorized source,” she said. “And the information gathered by the AI system will only be as good as the person who entered that information in the first place.”

Richard Rudman, the chair of California’s SECC, said Craig Fugate’s involvement lends a great deal of credibility to the project for him. Fugate also is former director of the Florida Emergency Management Division.

“AI is coming into our lives whether we like it or not,” Rudman wrote in an email. “I would hope before we let AI into the front door of alert and warning that some thought is given to the implications both good and bad.”

He said many emergency managers do not “use all the tools in their toolbox,” specifically referring to using EAS. “(EAS) is still a great and last resource that must be preserved to help protect those at risk when cell phones and Internet are taken out by disasters.”

Mike Langner, chair of the New Mexico SECC, said the Futuri system raises the usual questions about the dependability of AI.

“Given that the AI role in the Florida implementation is limited to communications — primarily to text-to-speech conversion with multi-lingual capability — not much could go wrong. If, and this is a big if, the instructions that an AI system is to disseminate to the public are clear and comprehensible, AI’s language ability can be a great time-saver,” he said.

He says using AI to translate the message means it must be “quality-controlled for accurate translation to make sure the message is accurate and timely is critical in emergencies.”

However, Langner openly questions if AI’s involvement will stop there. “If AI, at its current stage of development, is given a significantly greater role in alerting, hazards abound,” he says.

Another alerting expert says AI is already being used to a certain extent in the existing EAS. AI in emergency notification is being used to figure out to which stations what emergency messages should go, and in what language they should be provided when the hazard is in a multi-lingual area, this person said.

“If the AI system has true and proper knowledge of which media outlets reach which populations, and if AI knows the language and culture of those populations, it can certainly be a valuable, time-saving tool,” one EAS observer said.

“But will the AI knowledge base be kept up to date? AI can only know what it’s been taught or trained on. Everything else is pattern discernment that the AI program deems to be correct, and sometimes, perhaps in very critical times, isn’t.”

Lowell Kiesow, chief engineer for KNKX(FM) Public Radio in Tacoma, Wash., is vice chair of that state’s SECC. He said a service like Futuri’s seems to make perfect sense for Florida, where there is a propensity for severe weather. However, he continued, private/public systems typically have a downside.

“Unfortunately, such services come at a high cost, and many states and local governments just don’t have the money for public warning systems. EAS fills in because it can be made to work effectively without much cost,” Kiesow said.

He said the language capabilities of BEACON are intriguing.

“Multi-lingual alerting is a technical challenge for EAS and WEA, for which we haven’t had any good solutions. Message originators are hard pressed to just get the alert out in English, let alone multiple languages. And computerized language translation, as we’ve known it in recent years, just isn’t good enough to trust with public warning. Too many details get mangled in the process.”