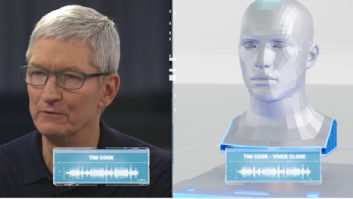

As heard in movies and on TV shows, the stereotypical computer-generated voice sounds awkward and unnatural. But thanks to artificial intelligence, today’s computer-generated voices can sound remarkably authentic and natural, especially if the voice has been generated after analyzing numerous samples of an actual person’s spoken words.

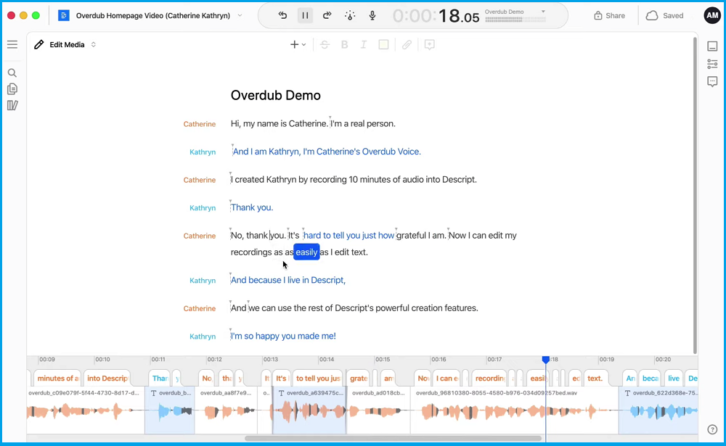

This is the approach being used by text-to-voice companies such as Descript. Billed as a tool to help podcasters edit and generate new speech simply by editing text transcripts, Descript starts out by having its clients read text samples into the company’s database, so that its AI-based text-to-voice engine has accurate sounds to work with.

“You can even create a range of delivery styles using samples of your voice,” said Jay LeBoeuf, Descript’s head of business development. “You could have one file labelled ‘Excited,’ a second labelled ‘Contemplative’ and so forth. Then when you input text that suits a particular style of read, you can tell our system which delivery style to use.”

The ability to create voice tracks from text, without actually stepping up to the microphone and speaking into it, has tremendous implications for the radio and voiceover industries.

In particular, the ability to create audio content from AI-generated “stock voices” (rather than cloned from individual human voices) could turn the market for human announcers upside down.

How good is text-to-voice?

This article was prompted by a Descript email received by Radio World with the subject line “Create Realistic, Synthetic Voiceovers Just by Typing.” It included a link to an audio file named “Descript Stock Voices.” It featured some of the 10 distinct AI-generated female and male voices that Descript offers to its text-to-voice clients for free. (A link to the audio file is at the end of this article.)

The file featured these non-human voices bantering back and forth, to illustrate how natural they sounded to the actual human ear. Again, their spoken words were generated directly from text.

In the subjective assessment of this writer, the AI-generated voices generally did sound authentic, although the need to leave distinct spaces between each of their words added a slight unnaturalness to the delivery.

Overall, the interplay between Descript’s AI-generated voices was impressive. In a short commercial or an on-air announcement consisting of two or three sentences, they would have been good enough to pass muster with most listeners.

Aimed at human announcers

Despite its mention of AI-generated voices, Descript says its services are aimed at human announcers/producers who want to make changes to their recorded content without having to go back to the studio.

“The most common use case for our Overdub voice cloning service is editorial corrections of human-delivered audio content,” said LeBoeuf. “It allows producers to make changes to this content as needed quickly and accurately.”

Sam Sethi is a U.K.-based radio presenter heard on Marlow FM, BBC Berkshire and several other radio stations. He also podcasts and does voiceovers, and uses Descript Overdub as part of his production process.

“I read Descript’s prescribed text to train their system for 30 minutes, and then Descript created my unique Overdub voice,” said Sethi.

“In a blind listening test, my wife of 20 years couldn’t tell with 100% accuracy which was the synthesized voice and which was my own. I was genuinely amazed by that. Since then I have used my Overdub voice to make small edits or add additional audio quickly by using Overdub.”

Possibilities

As useful as Descript’s Overdub voice cloning is to human announcers and products, it’s the economical AI-generated voices that might get a cost-sensitive radio manager thinking.

Using a text-to-voice portfolio of AI-generated voices, a network could create individualized news, weather and sports casts for each market. The text would be generated by humans at a central location. Stories would be sorted and stored in online folders for each station, organized by playout order and then fed to a text-into-voice system that would generated market-specific audio broadcasts for each location. No announcers required.

In the same vein, station identifications and other branded content that are being created by human voiceover artists could be produced using text-to-voice. (To offset any cadence issues, the station could openly acknowledge that it is using a text-to-voice system: “Hi, I’m Bob, your friendly AI announcer.”)

Meanwhile, local ad campaigns could be changed constantly as required using text-to-voice, allowing stations to provide an unprecedented degree of custom messaging to sponsors.

Fans of human creativity in radio are shuddering right about now. But these scenarios certainly seem credible in an era when big media companies have been known to cut costs.

According to Rolfe Veldman, CEO of www.Voice123.com, an online marketplace for voiceovers, AI-generated voices are already turning up, mainly in advertising.

“There’s an increased trend towards short radio ads and more of them in a given campaign, which is ripe for AI in my opinion,” Veldman told Radio World.

“Meanwhile, the quality of AI-generated voiceovers is improving. Six months ago it was horrible and today it’s already more than okay. So you can only imagine how good it may be in a year from now as the AI-enabled text-to-voice systems continue to improve.”

Veldman says he isn’t concerned about AI-generated voices displacing human announcers in general. But he does worry that the low cost of AI voices will further depress rates for human talent.

“There are already more voice actors available today than there is available work,” Veldman said. “Adding AI to the market will only make things challenging.”

Limit to the technology?

Now that AI-generated voices are here, it seems unlikely that they will disappear. But can a voiceover generated by an AI software program ever match the very best work done by a human?

Gary Kline is a veteran engineering consultant and contributor to Radio World. He’s not convinced that AI can do the job.

“The AI voices are good enough to use for weather, sports, emergency alerting, giving the time of day, and other short-form informative material,” Kline said.

“But I do not think that they are ready to replace your AM or PM drive host. I don’t think they will be voicing commercials either, at least not yet. It remains to be seen if anyone will actually use the technology for true air-talent replacement and if they do, if listeners will accept it.”

Joan Baker is vice president of the Society of Voice Arts and Sciences, and she is similarly skeptical of AI-generated voiceovers.

“I can see this technology being useful to producers who think they can’t afford the minimal cost for hiring skilled voice talent, and are working on projects where there is no real need to appeal to the emotions and needs of the intended listener,” said Baker.

“Selling to people, however, requires cutting through a very dense layer of cynicism and apprehension. This is why the ‘conversational, natural, non-announcery’ style of voice acting has become so popular.

“Beyond selling, it is also tough to communicate critical issues about public safety, health and many personal concerns over which consumers — the public — are looking for inspired solutions and advice,” Baker said.

“In these cases, only real people can tap into the nuances of emotions that are symbiotic in how people think and feel during one-to-one communications with each other. Can a robotic voice know the difference between saying ‘I love you’ at a time when a person feeling romantic toward his soulmate, and when he is being comforting a friend on their death bed?”

It is hard to imagine that an AI-generated voiceover could surmount the communications challenges outlined by Baker and Kline. That said, not so long ago it would seem unimaginable that AI-generated voices could pass for human. You can assess for yourself how close the Descript Stock Voices audio file gets.