A couple of years ago in these pages, I told the story of the worst lightning damage to a transmitter site that I have ever seen.

In the dead of a Michigan winter, lightning struck the 500-foot tower for our Detroit FM station. It traveled down the tower, followed the transmission line inside to the transmitter, then ran across the transmitter chassis looking for a path to ground. It found several, one of which was through the AC power connection to the transmitter, vaporizing all 14 of the fuse holders mounted on the front of the power supply cabinet of the Continental transmitter.

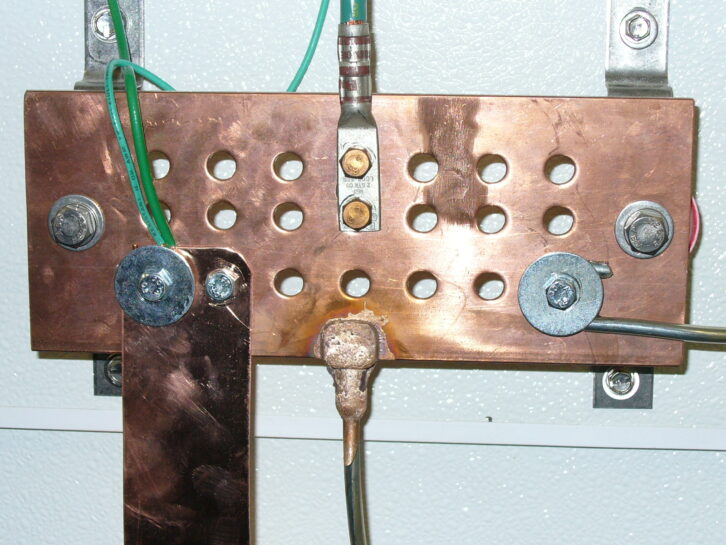

As I told you then, that lightning event showed us a severed ground strap that should have carried the energy from that strike safely into the ground and away from our equipment. It taught me to make checking ground connections, particularly at tower bases and building entry points for transmission lines part of the regular site inspection routine.

In the years since, these inspections have shown up stolen ground conductors and ground bus bars at sites. Thankfully we found the issues before something awful happened in each case.

It’s here!

I mention this again for a couple of reasons.

One is that “lightning season” is upon us in the northern hemisphere. Spring tends to bring thunderstorms in many parts of our nation. We get most of our severe weather toward mid-summer where I live in the Rocky Mountain region. But wherever you call home, the coming of spring is a good reminder to check grounds, ground conductors, grounding blocks and bus bars, TVSS modules and whatever other measures you have in place.

Another reason is that copper theft is again on the rise.

Seems like it took a break for the past couple of years, with copper prices dropping into the $3 per pound range. Now that they’re well over $4 a pound, copper is back on the radar of thieves. Heavy ground blocks, bars and conductors are very attractive targets.

The trouble for us is that there’s no immediate indication that our facility’s grounding has been hit in most cases. So here’s your reminder to add that back in to your visual inspection checklist (if it ever came off).

Another thing I have learned over the years about lightning strikes is that even with the best-grounded tall metal objects, all that current to ground creates a heck of an H- (or magnetic) field while the current is actually flowing. That H-field can do all kinds of mischief as its lines of flux cut conductors in the area.

Back in the late 1980s, I took a direct lightning hit to the amateur radio tower in my backyard. The simultaneous blast of thunder was LOUD and very sharp, and just about stopped my heart!

[Subscribe to Radio World Engineering Extra]

In addition to the screaming smoke alarms and ruined radios, that strike turned our television screen purple. Every image on the screen was purple. I knew exactly what the cause was, and thankfully I had a degaussing loop that I was able to run over the screen and get the colors back right, but it was a good object lesson on the intensity of that H-field.

On many occasions since, we’ve taken hits on various towers at studios and transmitter sites, towers that were well grounded and where the lightning current was shunted safely off to ground without going through any of our equipment — and yet we still took damage. The harm was entirely to components and devices that were connected to runs of audio, AES or network cables.

In an earlier analog age, we would see input and output op-amps get blasted. In more recent digital days we see switch ports and NICs get damaged. Why? It’s because those very intense lines of magnetic flux cut the conductors in audio and network cables and induce a damaging current into the conductors within. That current has to go somewhere, and that somewhere is equipment inputs, outputs and network ports.

What’s an engineer to do?

There are things that can be done to mitigate this kind of damage.

You can place ferrite cores on network and audio cables. You can use shielded cables; you can run cables in an EMT conduit.

Snap-on ferrites of the type often seen on wall-wart power supplies and other computer cables to maintain Part 15 compliance are relatively cheap and readily available from your favorite electronic component supplier.

There are network surge suppressors available, some of which are very good, but it’s impractical to put one on every network cable.

Perhaps the best thing to do is evaluate your facility for the most vulnerable cable runs and protect those with ferrites and conduit. Otherwise, keep spare parts on hand, including shelf spares of your core network switches, all configured up and ready to swap out in a hurry if the worst happens.

The sad truth is that the only way to “lightning proof” a piece of equipment is to put it under the bed where you’re sleeping. That way, the lightning has to go through you to get to it. It might still get through, but if it does, it won’t matter to you!

In the latest issue of RW Engineering Extra, Steve Walker of Wheatstone gives us some great pointers on protecting our studio and transmitter facilities from lightning damage. His tips provide a benchmark for evaluating our facilities to be sure we’ve done things right, hopefully before we find out the hard way that we haven’t.

Also, Tom Vernon provides a look at the NAB’s Pilot Radio Test Bed, which you — yes you! — can use to evaluate the performance of various devices under differing conditions.

So check those grounds and settle in for a good read. We hope you’ll learn something.