Nick’s Signal Spot is a new feature in which Nick Langan explores RF signals, propagation, new equipment and related endeavors.

A couple of months ago, I wrote about tunnel radio.

It is really more of an underground type of carrier current, a method used for years to broadcast on college campuses for example.

Numerous universities created what were in essence closed-circuit radio stations, particularly to serve student needs. Usually, the output of a low-power transmitter was coupled to a dorm’s standard electrical wires, but a dedicated broadcast loop could also be used.

According to 35000watts.com, Brown University’s “Brown Network” carrier-current station was the first such station, in 1936. Later, the technology was used in some U.S. cities via overhead power lines, during World War II, to avoid enemy broadcast eavesdropping.

At my own alma mater Villanova University, a group of electrical engineers decided to start a station during the school year of 1946–1947.

As an exhibit put together by the school’s Falvey Library explained, the students used their own time, money and equipment to set up their station in a linen closet on the third floor of Austin Hall. At the end of 1947, the station began broadcasting on 538 kHz as WVIL.

The operation ultimately moved to 640 kHz, a popular carrier-current frequency, and served Villanova until 1991, when the school procured an FCC license via a timeshare with the former Cabrini University.

Dan Braverman, founder and president of Radio Systems in Philadelphia, has a wealth of experience with carrier-current systems. He told us that Pennsylvania company Low Power Broadcast, or LPB, commercially produced the first 2-watt, 6-watt and 20-watt transmitters for carrier current. The company was founded by former college professor Dick Crompton.

Braverman worked alongside LPB doing site surveys on hundreds of college campuses to determine the best transmitter locations and electrical system wiring.

Carrier current deserves its own rabbit hole, and one of our readers delivered.

WMMR at the University of Minnesota

Retired broadcast engineer Archie Stulc went back to his days in the early 1980s studying at the University of Minnesota. The university itself owned a full-time AM, 770 KUOM(AM).

But there was the student operation, “WMMR” — Women and Men’s Minnesota Radio — sent via the carrier current that ran in eight dormitories, on 730 kHz. It is not to be confused with the long-time commercial station in Philadelphia, WMMR. (No FCC call signs are assigned to carrier-current stations, of course.)

A twisted pair of audio wires ran from the studios in the Student Union building to a transmitter in each dorm.

“This pair went to Sanford, this pair went to Middlebrook,” Stulc went on.

He believes the wiring went back to early days of the station. The station itself, according to a timeline on the KUOM website, dates to 1948.

Garrison Keillor, host of Minnesota Public Radio’s “A Prairie Home Companion,” got his start on the station.

If students wanted to do a remote broadcast from a dorm, Stulc remembered, they would tap into the station’s program phone lines. Each dorm had its own transmitter, and the wires ran through steam tunnels to each building. (For this reason carrier current also is sometimes referred to as a “steam-tunnel network.”) Every once in a while, if a dorm went offline, they’d find that a worker in the steam tunnels had snagged onto a line and broken one.

In all, the cables covered at least two miles, making it difficult to identify sources of outages.

“We could only tap in at the main power supply in the sub-basement, so that caused some problems — like finding someone to let us down there!” Stulc said.

The dorm’s electrical wiring ended up being the station’s antenna. One building ended up being one wavelength tall. “So in the middle floors, you couldn’t get us.” Turning on a light could change the signal quality.

How did Stulc and his collegiate colleagues maintain the operation?

They would go by each dorm on a regular basis, tuned to 730. “We wouldn’t know if someone was off the air otherwise,” he said. As his time at U of M went on, they began to upgrade their equipment. He remembered its HFOF or “Hell Froze Over First” air console, named for how long it took to assemble its circuitry.

The two stations — WMMR and KUOM — would end up uniting in 1993 as “Radio K.”

Drive-in delights

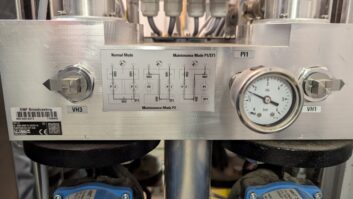

Stulc was reminded of a carrier-current transmission approach called leaky coax, also used in tunnels.

“You remember the old drive-in theaters?” he asked me.

Many of them did not want to maintain the boxes that would attach to your window and might rip off, separating them from their wires, if the driver departed their cinematic experience early.

So they would maintain a carrier-current feed to a “leaky” coaxial cable that was designed to intentionally radiate RF energy along its length. The cable ran around the patron parking area.

“I’m sure the concession workers made a few extra dollars once in a while jump-starting someone’s car that ran the battery down,” he reminisced.

Stulc’s engineering career included years at 1280 WWTC(AM) in Minneapolis.

More on L.A. tunnels

We also followed up with a letter from Ben Dawson on the Los Angeles International Airport tunnel-radio system.

Engineer Burt Weiner remembered another deployment on the I-110 Pasadena freeway, just north of downtown Los Angeles.

“AM radio would be pretty much lost in those tunnels,” he said. There are four northbound-traffic tunnels, also known as the Figueroa Street Tunnels.

In order to solve the problem, the City of L.A. ran wires on stand-off insulators through each of the tunnels, he explained. For each tunnel, the outer conductor of the coaxial cable was connected together forming a loop over the top of the hill. Weiner said that each of the tunnels had its own loop.

“It worked quite well,” he said.

The remnants of the system can still be seen, but it fell into disrepair years ago and is no longer functional.

“With very few exceptions, almost all AM signals, once again, completely disappear in the tunnels,” Weiner said.

The “Big 8”

Kevin Curran noted that CKLW(AM) in Windsor ran a wire antenna through the vent system of the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel in 1971. He dug up a Bob Hamilton Report from David Gleason’s World Radio History website that detailed the 20-year contract Alden Deihl and Company was awarded to beam 800 kHz — then “The Big 8” — through the tunnel.

There was a billboard above the entrance reminding drivers that the one station they could hear was CKLW.

Neither U.S. nor Canadian regulators found a problem, Curran said.

Radio World welcomes letters to the editor on this or any story. Email [email protected].