Darren Morton is the radio director for Grove City College’s WSAJ(FM) in Pennsylvania.

The station covers a lot of high school football games, and most of the schools don’t have an extra phone line in their press boxes. This relegates Darren and his staff to the dreaded cell phone interface for many of the games.

A couple of years ago, the college switched cell phones, purchasing a Nokia unit that offered much better RF performance. Its only drawback was a goofy four-pin mini plug for audio interfacing.

Darren bought an adapter to convert the standard 1/8-inch TRS (tip, ring, sleeve) plug to the Nokia four-pole. It quickly became a point of failure due to intermittent contact issues. The intermittent adapter also would not reliably keep the phone in ear-set mode, further interrupting broadcasts.

Darren tore that adapter apart — completely destroying it in the process — and found a tiny PCB with a couple unidentifiable parts on it. Some experimenting with the trusty Fluke 177 on the broken parts and pigtails into the phone revealed that the mic element was balanced, hence the extra pole on the connector.

He grabbed an old Nokia ear-set and lopped the mic and ear piece off. Inside the jacket were a red wire with shield, and white wire with a shield.

The send audio (mic input) was white, and the receive (Cue audio) was red. Darren used the new pin out and made a ¼ / XLR-to-4-pin adapter to plug into their JK Sport Mix …but had no luck.

The next step was to check another Nokia ear-set and put the Fluke to it. As it turns out, there needs to be a 10k resistance across the white wire and shield in order to put the phone into ear-set mode. With a resistor in place, the adapter worked fine.

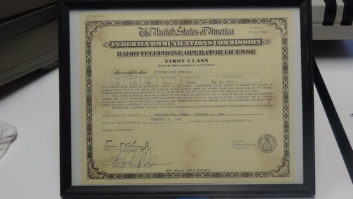

(click thumbnail)Fig. 1: Here’s the adapter Darren Morton prepared for the Nokia Cell Phone.The only adjustment needed after that was a 10 dB pad on the JK’s output, which fed the cell phone. Darren’s modification schematic is seen in Fig. 1.

Darren admits to a certain amount of pleasure in hacking apart and/or destroying anything related to cell phone “technology,” but the efforts paid off. Thanks for the tip, Darren.

* * *

Mike Heim is an engineer for the Youngstown, Ohio, Clear Channel cluster, and a VHF amateur operator. He’s been active over the years in dealing with VHF propagation and wanted to share some points with Workbench readers.

There are a number of propagation modes that have the possibility of affecting FM broadcast radio. Tropospheric enhancement is only one of them, but it usually occurs mostly in the summer and fall.

The Hepburn maps, discussed in the Sept. 26 column, are predictions of these conditions, and are sometimes accurate. However, Mike also uses another tool as “evidence” that tropo is actually happening in real time.

The web site is www.mountainlake.k12.mn.us/ham/aprs/path.cgi?map=na

This map uses actual amateur radio beacons which crisscross the nation and southern Canada. It displays real-time enhancements on the 144 MHz amateur band, and is a reliable indicator that tropo is occurring in your area in real time. The nature of tropo is such that it occurs on higher frequencies and works its way downward.

There is another effect that affects the FM broadcast band, and it is confused with tropo, but it is entirely different. Hepburn’s map will not show this type of propagation, but the above site may. Mike is referring to a condition known as “Sporadic E,” which affects lower frequencies and moves upward.

This propagation occurs in the springtime months. When the effect is in full swing, it produces extremely strong signals from distances of about 800–1,200 miles. The effect is strong enough that DX stations have the strength of a local station. This propagation is really not predictable, except that it occurs usually between May and July.

Signals are typically much stronger on the 100 MHz band than a typical ducting opening. They can occur anytime, but from about 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. local time the effect is the most intense. It is caused by an ionization of the E region of the ionosphere (about 60 miles in altitude), and its causes are unknown. There is no relationship to sunspot activity that causes ionization of higher ionospheric layers.

Many interference complaints are confused with tropo, but depending on the time of year and time of day, we may be dealing with something totally different, and the Hepburn maps may show flat conditions, but yet we hear stations coming in from all over the country.

Therefore, Mike uses both tools to determine what is really going on.

We appreciate the additional resource.

(click thumbnail)Fig. 2: A different method of mounting an ATU.* * *

Hal Kneller of Harris has been a friend to this column for years, providing troubleshooting, maintenance tips and interesting photos. Fig. 2 was sent to Hal by Chuck Lakaytis, director of engineering for Alaska Public Radio.

Because it’s almost impossible to get concrete work done in rural communities, where KOTZ(AM)/Kotzebue is located, engineer Ron Zastro came up with this deck design to keep the new Kintronic 10 kW antenna tuning unit out of the mud. Adjustable Arctic legs will be installed next spring, making the installation permanent.

The ATU includes phase rotation for proper load matching and best HD performance on AM.

The design certainly keeps the ATU out of the mud, but we agree that Ron has a great “second career” designing and building decks, should he so desire.