“That’s going to do it for another fantabulous ‘GO’ radio program, a happening phase number two, and we’ll do the whole thing over again tomorrow night at 2100 hours.” — Harry Simons on American Forces Vietnam Network, 1969.

Harry Simons works the mic at AFVN Danang in 1969. For 13 years in the 1960s and 1970s, American Forces Vietnam Network comprised a group of radio and TV stations with their headquarters in Saigon and local stations or “detachments” in Danang and several other cities. AFVN was an arm of the U.S. Department of Defense’s Military Assistance Command Vietnam and was supported by Armed Forces Radio and Television Service in Los Angeles.

For most American civilians, their introduction to AFVN came via 1987’s film “Good Morning, Vietnam” starring Robin Williams as the exuberant disc jockey Sergeant Adrian Cronauer. But that was a Hollywood depiction. To get a flavor of what it was really like, talk to another man who worked in AFVN radio in the late 1960s, Marine Corporal (later Sergeant) Harry Simons, who in 1967–68 served as chief engineer and announcer for the Saigon stations and in 1969 as an announcer at the AFVN Danang detachment.

The stories of this network, and many of those involved with it, are told in an ambitious 10-hour audio documentary, “AFVN: the GI’s Companion,” that aired recently on WEBY(AM) on the Gulf Coast of Florida and can be heard online. Simons played a key role in the production and provided much of the vintage audio.

The AFVN detachment in Danang, 1969. Featuring fresh interviews alongside airchecks that had not been heard in almost 50 years, the show takes listeners back to the Johnson and Nixon presidencies, a time when the cost of a typical new car was under $3,000, a serviceman could expect 10 percent interest on his savings account, and terms like “groovy” and “far out” were uttered without irony.

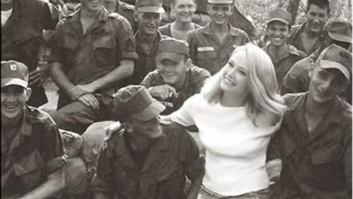

Included in the program are radio luminaries Scotty Brink, Scott Manning, Dick Orkin, Gary Gears, Chris Noel, Pat Sajak and Adrian Cronauer.

During the Vietnam War, AFVN played hits by The Doors, Steppenwolf, the Beatles and other artists, providing a little touch of home for the 3 million or more American servicemen and -women stationed there. In place of commercials, listeners were treated to government-sponsored reminders to clean one’s weapon properly, take malaria pills, change socks frequently, refrain from shipping home items purchased in communist countries and avoid marijuana.

For many men and women, AFVN was the soundtrack of the war in Vietnam — and an immediate morale-booster.

WORK HAZARDS

Straight out of high school, Simons signed up for a tour of duty with the Marines. After arriving in Vietnam in 1967, he found himself at AFVN in Saigon where his first job was chief engineer, a post for which he admits he was unqualified at the time.

“Fortunately my job was primarily administrative, and we had good support from American civilian employees and locals who were real engineers,” he relates in the documentary. “Also, the equipment was brand new, so we had relatively few technical problems.”

Of course, the bombings presented challenges.

Mike Bates stands in front of a rooftop structure, once part of a CIA residence, familiar from 1975 news coverage of the evacuation of Saigon. He holds a photo of the spot taken during the evacuation. “AFVN was one of the top three primary targets of the enemy in Saigon,” Simons told Radio World.

“Inside our fenced perimeter compound in Saigon AFVN was co-located with the South Vietnamese radio and TV stations separated by a single chain link fence in the middle of a large concrete driveway. Several attacks occurred targeting at each of the facilities separately.”

In the documentary a recording of one such attack in 1968 is included, narrated by Scott Manning. That attack was 250 pounds of plastic explosive delivered to the AFVN side of the compound in a taxi cab.

“The blast caused considerable damage to the front and one side of the building. Ceiling tiles and fixtures collapsed throughout the building onto people and equipment and many windows were blown out, glass was everywhere. A similar attack was launched at the South Vietnamese facility later in 1968. The extremely close proximity of the two facilities allowed for collateral damage.”

Both Simons and his colleagues endured those and other attacks. Not the kind of work hazard one typically meets in a U.S. broadcast facility.

Later in Saigon he added the job of disk jockey to his duties, hosting the nightly “GO Show,” a request rock and roll program. Simons belted out the hits for anyone listening throughout Vietnam and 13 other countries.

Norm LaFountaine was a helicopter crew chief stationed near Danang in 1968 and ’69. In the documentary, he discusses the importance of AFVN to the spirit and the motivation of the troops.

“One night we were flying a Medivac mission and it was raining like crazy and it was cold,” said LaFountaine. “I dialed in AFVN, and here comes Sam and Dave singing ‘Hold on, I’m Coming,’ and that’s what we were doing, coming to get these guys. That always stuck in my mind.”

The modern interviews heard in the documentary were recorded by Simons and WEBY Program Director Mike Bates; the task of assembling the elements fell to Bates.

“I had known Harry for about 13 years,” said Bates. “He mentioned that he had many hours of tapes of himself and others on the air from the Vietnam era and asked if I’d like to hear one. Out of curiosity I listened and my reaction was, ‘Hey, this guy was really good!’ But as I heard more of the tapes, I recognized the historical significance of them and thought they should be shared with the world. That’s when we decided to work on this project together.”

Bates and Simons, third and fifth from left, tour a TV studio in Saigon where AFVN once operated.QUIET, TOO QUIET

The project afforded Simons a chance to go back not only in spirit but in body. In September 2015, he and Bates made an 18-day research trip to Vietnam. For Bates it was a first visit; for Simons it was an eerie return to a strange yet familiar land.

“The first reaction I had was an immediate flashback to 1967,” he said. “I wasn’t sure I wanted to get off the plane, and I was dazed for some time. I thought, ‘Oh my God, what am I getting into?’ My whole body was shaking.”

Even within the safety of his hotel Simons was uncomfortable.

“I didn’t feel secure at all,” he said. “I had to keep reassuring myself that a war was not going on. It was so quiet. When I was there the first time there were constant sounds of bombs, rockets, mortars and small arm fire and now none of that was taking place. Where was the war?”

Of course much had changed in the nearly five decades since Simons had seen the city. The airport was modernized and the AFVN building had morphed into a TV digital production facility owned and heavily guarded by the government. It took complex negotiations with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs before the duo was allowed inside the station.

When Simons and Bates were allowed to visit the building that had housed AFVN, they were escorted by a polite group of Ho Chi Minh City Television employees, some of whom had worked there for many years. Simons was told he was the first former AFVN staffer to enter the facility since its evacuation in 1975. He found it a good ending to a difficult journey.

LISTEN NOW

Bates said most of his job on the documentary was done in an air-conditioned radio studio in peaceful northwest Florida. “The real credit and glory should go to the people who served in Vietnam. After the documentary aired we got a lot of phone calls and emails from veterans who remembered listening to AFVN. It brought back memories for them, good and bad, but they really enjoyed hearing it. If there was a good part of the war in Vietnam for these guys, it was AFVN.”

The documentary originally aired in two-hour segments over five weekdays in October, commercial-free; it was rerun on Veterans Day and streamed live over WEBY’s website both times (www.1330weby.com). You can hear the full 10-hour audio documentary at http://rockradioscrapbook.ca/afvn.html.

Bates, left, and Simons discuss AFVN in the WEBY studios. “This isn’t about the sound of the war itself,” Bates says in the program’s opening minutes. “It’s about the soundtrack of the war. AFVN was heard everywhere: on bases, in hooches, in trucks, aboard ships, in cockpits, and even in the fields of battle. Wherever Americans were, AFVN accompanied them.”

Much of the top 40 music in the program’s vintage sections will be familiar, though there are plenty of forgotten gems too. Part of what sets the show apart are the fascinating DJ patter, the jingles and the government-sponsored PSAs programmed with the serviceman in mind.

We hear “boss radio” jocks celebrating “million dollar music for the Aquarian Age.” The National Center for College Admissions promises to submit a veteran’s college application to more than 100 colleges. Servicemen wondering where to spend their R&R hears a spot pitching Hawaii, where “the ‘mod’ sound is in! Hawaii after dark is grooving to the ‘now’ sound of today!” And a memorable PSA warns of the dangers of pot: “You know what the VC and NVA do when they get ready to go into battle? They get high, man. Yea, they smoke grass. Then they don’t care if they die or not.”

With its extended-aircheck format, “AFVN: the GI’s Companion” is something of a time capsule not only of AFVN but American life in the late 1960s.

However, Simons emphasizes that the show is also about much more than music and jocks. Nine months of careful research went into its planning.

The program features an interview with Lyn Watkinson, a “pen pal” in the United Kingdom who wrote to U.S. servicemen in Vietnam; hundreds of letters to her are in the British Museum of History in London.

There’s also a 1969 interview with an officer of charge of a special operations outfit assigned to defoliation using Agent Orange; a recent interview with Harry Ettmueller, the only surviving POW of the attack and annihilation of the Hue, Vietnam, AFVN detachment; and a recent interview with West Point Professor Greg Daddis, speaking about the version of the song “White Christmas” played by the one remaining FM station in Saigon, to signify the final evacuation on the morning of April 29, 1975.

Said Simons, “It is a story that has never been told in this manner.”

Ken Deutsch is grateful to Sergeant Simons and all the men and women who have served in the American forces. Former AFVN staffers connect with each other on Facebook, in a Yahoo group and via frequent reunions. Much more about AFVN can be found at www.afvnvets.net/home.html.