At the turn of the millennium, the growing popularity of streaming media inspired the development of “internet radios.” These standalone appliances were styled to look and work like conventional AM/FM radio receivers while tuning into streaming audio feeds from the web.

This fusion of familiar functionality with web-based content seemed like a slam-dunk for the consumer electronics market, and many manufacturers started selling them to the general public.

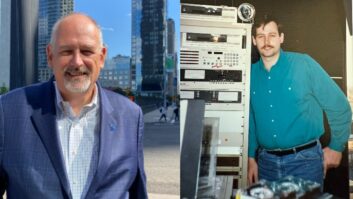

“The market was very bullish, as there were not many connected products at that time,” said Greg Fadul, CEO of Grace Digital, which designed its first internet radio in 2008 and continues to make and sell them.

“They were very focused as a replacement for the standalone radio receivers we had in our homes at that point,” said radio futurologist James Cridland, who managed streaming content for Virgin Radio and the BBC, and worked for a time with internet receiver manufacturer Pure.

“Instead of having a receiver that did AM/FM, ‘this one does internet radio’ — with access to thousands of stations across the world.”

From time to time over the past 20 years, Radio World has checked back in on this industry segment. Today, you can still buy internet radios from companies such as Grace Digital and C. Crane. But the days of these devices being touted as The Next Big Thing are past.

Pioneering Players

In the early days of the trend, there were lots of manufacturing pioneers looking to stake their claim.

Grace Digital was one, said Fadel, along with Roku and SLIMP3 — subsequently Logitech Squeezebox. “They offered basic internet radio services and local/network media players.”

C. Crane was another trailblazer. “We carried our first internet radio in 2006, and manufactured our first in 2008,” said CEO Jessica Crotty. The company’s CC WiFi 3 is the third generation of that 2008 model.

“The first internet radio we carried was the Acoustic Energy WiFi Internet Radio. The other brands we carried were Revo and Tangent. Our focus was standalone radios that worked out of the box; and we had one that was ‘portable.’ Most had some standard radio functionality such as clocks and alarms and presets as well. I know there were others we tested back then, but many had software to load or were super complicated to set up.”

European DAB radio manufacturer Pure was active as well, and still sells internet radios.

But many others are gone. One of the fallen is the iM tuner, a piece of software on a Windows machine that also had a Bluetooth tuning attachment, Cridland recalled.

“Radio stations were given a specific number on the band, with the hopes that you’d say ‘FM 107.9, iM 466.’ The predecessor of TuneIn, called RadioTime, was a similar device that plugged into a computer to give a hybrid approach of FM radio and internet radio,” he said.

“There were also a number of cheap Chinese imports, based on a specific chip with Wi-Fi connectivity. Some of these chipsets were used by premium radio receiver producers, like Roberts in the U.K. — the queen’s choice of radio receiver — to launch internet radios.”

The Logitech Squeezebox line also is gone, although the company remains in business. Logitech stopped making Squeezeboxes in 2012 and shot down the aggregation content platform that served streams to the remaining units — www.mysqueezebox.com — this year.

What happened

So while radios can still be purchased from the companies mentioned above as well as others like Revo, Sangean and Tangent, the technology never broke out of its niche to become a mass-market device.

The result? “Logitech got out of the market and others continued to go out, as demand was not recognized,” Fadul said. “Como Audio and Tivoli Audio were the most recent companies to exit the internet radio market, with Como Audio shutting their business down.”

What went wrong? Foremost, streaming media evolved into something that far surpassed the 20th century thinking behind standalone internet radios. Not only did it now include video, but streaming media became interactive and customizable while turning up as easy-to-access content on smartphones and smart speakers.

Internet radios — with their audio-only focus, reliance on proprietary content aggregation websites and their multi-step manual tuning systems — couldn’t compete.

“Honestly, the wide adoption of smartphones and smart speakers probably had the biggest impact on this, especially once they added radio listening capabilities,” said Crotty.

“In addition, the original internet radio content aggregators such as Reciva were built on old technology; and a lot of factors led to the closing of their operations. In some cases for aggregation platforms, a lack of recurring revenue makes it difficult to maintain the servers and programming required to keep up.”

Even before smartphones and smart speakers took off, there were a number of issues that prevented internet radios from becoming mass-market early on.

“Many people didn’t have Wi-Fi in their homes, so it was difficult to get connectivity to their radios,” Cridland said. “Many internet radios did have ethernet connections on the back, but ethernet connections weren’t easily available in many homes.”

Broadband internet service was also a must for using internet radios, which many consumers lacked.

“At the time when the Kerbango internet radio came out, my house in North London had an ISDN connection, which was 128 kbps in total, and cost me money to connect,” said Cridland. “I later managed to upgrade to an always-on 512 kbps connection, but that was after Kerbango stopped production.”

Then there were content shortfalls. “The online streams for stations weren’t high-quality audio — the BBC at the time was just 32 kbps — and many big brand names were not streaming online,” Cridland said.

“In the U.S., the costs of music rights meant that radio companies were actively dissuading their listeners from using the internet, since it cost more per listener. Rights issues meant advertising on internet radio was different from on AM/FM, and most radio companies did an awful job of filling the breaks competently with anything approaching decent content.”

He said it wasn’t unusual to hear the same ads twice or three times in a stopset, or for actual programming to cut off.

“Then the iPhone came out, and there was no real reason for a standalone device anymore. And then broadcasters wanted listeners to sign in using their own apps, so they could get advertising and listener metrics, and then they actively neglected their raw internet streams.

“Also the user interface was awful, since it’s very hard to give people a simple straightforward interface into more than 10,000 radio stations. It also seemed to be beyond radio receiver manufacturer capabilities to make a device that merged AM, FM, DAB and internet in one user interface. Instead, listeners would switch between the bands and each band would behave differently.”

If these problems weren’t enough to stifle the popularity of internet radios, Crotty said, some internet radio stations blocked content because of licensing conflicts.

“Another thing that became challenging was when everyone came out with their own app. Then you had to get licensing or agreements to access the content, in essence making it more difficult for us to help customers listen to what they were trying to listen to.”

Andrew Wu, marketing director for Sangean, said that in contrast to the woes of internet radios, portable radios with traditional bands are easier to access without needing any additional connection.

“Cars equipped with HD and satellite radios are also quicker to connect. Internet radio is a great medium, but it’s always been for a niche crowd, due to all the other available and more accessible platforms and bands.”

Success in stealth mode?

Internet radios still seem to support a vibrant niche market.

“There are still a dozen small brands that sell internet radios,” Fadul said. “There remains a smaller population who want single-purpose devices, and those who enjoy a dedicated internet radio can easily obtain one. This is why Grace Digital’s internet radio business is solid. We do not see big growth in the market, but we continue to add features and update our platform periodically.”

Wu said, “I don’t believe there’s been a demise in internet radios, but all the options available today inevitably dilutes the usage time of any single feature. There is still a lot of potential for the internet radio market, as more countries are transitioning to digital-only devices and the populace is trending towards a quality listening experience.”

Jessica Crotty says the technology still has a future.

“There’s definitely a group of listeners who don’t want to listen on their smartphones. They don’t want to have to log in and provide personal information or have a ‘smart’ device that tracks them and what they do. They want decent sound quality and somebody else to have done the work for them of finding and organizing the stations so they can listen at their leisure. They also love having support when they need it.”

Now for a twist ending: “Smart speakers act very well as a standalone system to listen to live radio,” said Cridland. “In this regard, standalone internet radio receivers have never been more popular, because the overwhelming amount of use of smart speakers is for listening to live radio. So the truth is that smart speakers are actually internet radio receivers. They just look a little different.”